A feat of strength MVP for AI Apps

A minimum viable product (MVP) is a version of a product with just enough features to be usable by early customers, who can then provide feedback for future product development.

Today I want to focus on what that looks like for shipping AI applications. To do that, we only need to understand 4 things.

- What does 80% actually mean?

- What segments can we serve well?

- Can we double down?

- Can we educate the user about the segments we don’t serve well?

The Pareto principle, also known as the 80/20 rule, still applies but in a different way than you might think.

What is an MVP?

An analogy I often use to help understand this concept is as follows: You need something to help get from point A to point B. Maybe the vision is to have a car. However, the MVP is not a chassis without wheels or an engine. Instead, it might look like a skateboard. You’ll ship and realize the product needs brakes or steering. So then you ship a scooter. Afterwards, you figure out the scooter needs more leverage, so you add larger wheels and end up with a bicycle. Limited by the force you can apply as a human being, you start thinking about motors and can branch out into mopeds, e-bikes, and motorcycles. Then one day, ship the car.

Consider the 80/20 rule

When talking about something being 80% done or 80% ready, it is usually in a machine-learning sense. In this context, each component is deterministic, which means 80% translates to 8 out of 10 features being complete. Once the remaining 2 features are ready, we can ship the product. However, If we want to follow the 80/20 rule, we might be able to ship the product with 80% of the features and then add the remaining 20% later, like a car without a radio or air conditioning. However, The meaning of 80% can vary significantly, and this definition may not apply to an AI-powered application.

The issue with Summary Statistics

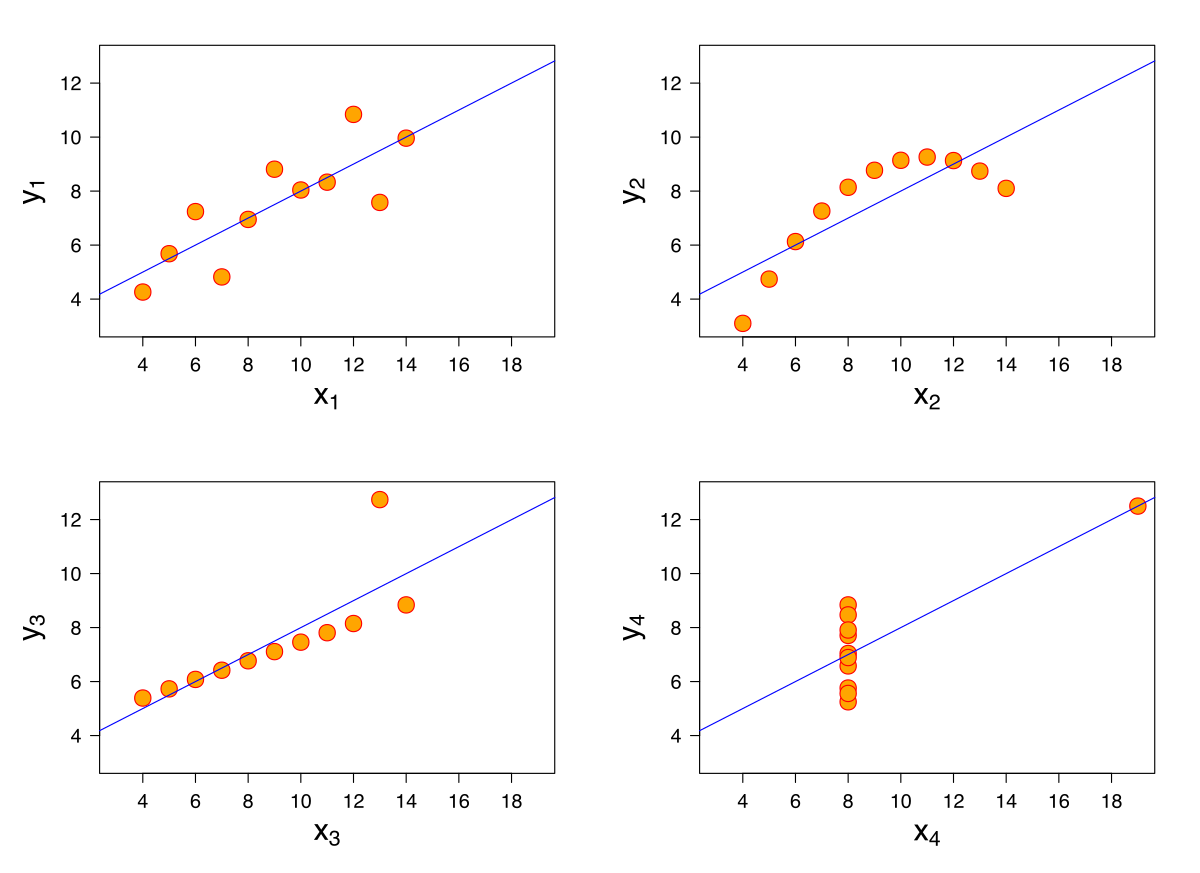

The above image is an example of Anscombe’s quartet. It’s a set of four datasets that have nearly identical simple descriptive statistics yet very different distributions and appearances. This is a classic explanation of why summary statistics can be misleading.

The above image is an example of Anscombe’s quartet. It’s a set of four datasets that have nearly identical simple descriptive statistics yet very different distributions and appearances. This is a classic explanation of why summary statistics can be misleading.

Consider the following example:

| Query_id | score |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.9 |

| 2 | 0.8 |

| 3 | 0.9 |

| 4 | 0.9 |

| 5 | 0.0 |

| 6 | 0.0 |

The average score is 0.58. However, if we analyze the queries within segments, we might discover that we are serving the majority of queries exceptionally well!

Admitting what you’re bad at

Being honest with what you’re bad at is a great way to build trust with your users. If you can accurately identify when something will perform poorly and confidently reject it, then you might be ready to ship a great product while educating your users about the limitations of your application.

It is very important to understand the limitations of your system and to be able to confidently understand the characteristics of your system beyond summary statistics. This is because not all systems are made equal. The behavior of a probabilistic system could be very different from the previous example. Consider the following dataset:

| Query_id | Score |

|---|---|

| 1 | .59 |

| 2 | .58 |

| 3 | .59 |

| 4 | .57 |

A system like this also has the same average score of 0.58, but it’s not as easy to reject any subset of requests…

Learning to say no

Consider an RAG application where a large proportion of the queries are regarding timeline queries. If our search engines do not support this time constraint, we will likely be unable to perform well.

| Query_id | Score | Query Type |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.9 | text search |

| 2 | 0.8 | text search |

| 3 | 0.9 | news search |

| 4 | 0.9 | news search |

| 5 | 0.0 | timeline |

| 6 | 0.0 | timeline |

If we’re in a pinch to ship, we could simply build a classification model that detects whether or not these questions are timeline questions and throw a warning. Instead of constantly trying to push the algorithm to do better, we can educate the user and educate them by changing the way that we might design the product.

Detecting segments

Detecting these segments could be accomplished in various ways. We could construct a classifier or employ a language model to categorize them. Additionally, we can utilize clustering algorithms with the embeddings to identify common groups and potentially analyze the mean scores within each group. The sole objective is to identify segments that can enhance our understanding of the activities within specific subgroups.

One of the worst things you can do is to spend months building out a feature that only increases your productivity by a little while ignoring some more important segment of your user base.

By redesigning our application and recognizing its limitations, we can potentially improve performance under certain conditions by identifying the types of tasks we can decline. If we are able to put this segment data into some kind of In-System Observability, we can safely monitor what proportion of questions are being turned down and prioritize our work to maximize coverage.

Figure out what you’re actually trying to do before you do it

One of the dangerous things I’ve noticed working with startups is that we often think that the AI works at all… As a result, we want to be able to serve a large general application without much thought into what exactly we want to accomplish.

In my opinion, most of these companies should try to focus on one or two significant areas and identify a good niche to target. If your app is good at one or two tasks, there’s no way you could not find a hundred or two hundred users to test out your application and get feedback quickly. Whereas, if your application is good at nothing, it’s going to be hard to be memorable and provide something that has repeated use. You might get some virality, but very quickly, you’re going to lose the trust of your users and find yourself in a position where you’re trying to reduce churn.

When we’re front-loaded, the ability to use GPT-4 to make predictions, and time to feedback is very important. If we can get feedback quickly, we can iterate quickly. If we can iterate quickly, we can build a better product.

Final thoughts

The MVP for an AI application is not as simple as shipping a product with 80% of the features. Instead, it requires a deep understanding of the segments of your users that you can serve well and the ability to educate your users about the segments that you don’t serve well. By understanding the limitations of your system and niching down, you can build a product that is memorable and provides something that has repeated use. This will allow you to get feedback quickly and iterate quickly, ultimately leading to a better product, by identifying your feats of strength.