Source: Menlo Ventures, 2025: The State of Generative AI in the Enterprise [1]

Source: Menlo Ventures, 2025: The State of Generative AI in the Enterprise [1]After reading Jaya Gupta’s post about Context Graphs, I have not been able to stop thinking about it [1]. For me, it did something personal: it gave a name to the architectural pattern I have been circling around in the agentic infrastructure discussions on this blog for the past year.

Gupta’s thesis is simple but profound. The last generation of enterprise software (Salesforce, Workday, SAP) created trillion dollar companies by becoming systems of record. Own the canonical data, own the workflow, own the lock in. The question now is whether those systems survive the shift to agents. Gupta argues they will, but that a new layer will emerge on top of them: a system of record for decisions.

I agree. And I think this is the missing piece that connects everything I have been writing about.

What resonated most with me was Gupta’s articulation of the decision trace. This is the context that currently lives in Slack threads, deal desk conversations, escalation calls, and people’s heads. It is the exception logic that says, “We always give healthcare companies an extra 10% because their procurement cycles are brutal.” It is the precedent from past decisions that says, “We structured a similar deal for Company X last quarter, we should be consistent.”

None of this is captured in our systems of record. The CRM shows the final price, but not who approved the deviation or why. The support ticket says “escalated to Tier 3,” but not the cross system synthesis that led to that decision. As Gupta puts it:

“The reasoning connecting data to action was never treated as data in the first place.”

This is the wall that every enterprise hits when they try to scale agents. The wall is not missing data. It is missing decision traces.

Reading Gupta’s post, I realized that the evolution I have been documenting on this blog (from MCP to Agent Skills to governance) is really a story about building the infrastructure for context graphs. Let me explain.

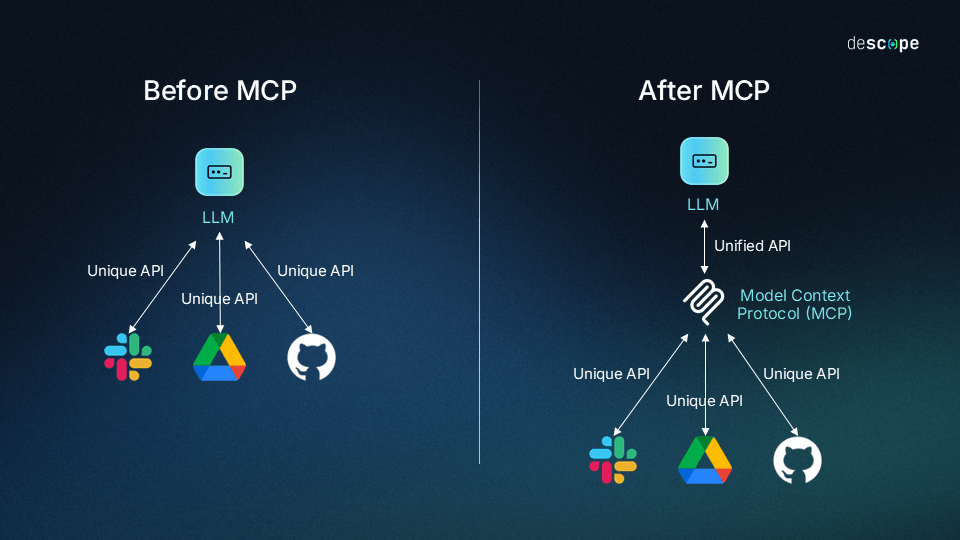

Phase 1 was about tools. The Model Context Protocol (MCP) gave agents the ability to interact with external systems. It was the plumbing that connected agents to databases, APIs, and the outside world. But we quickly learned that tool access alone is not enough. An agent with a hammer is not a carpenter.

Phase 2 was about skills. Anthropic’s Agent Skills standard gave us a way to codify procedural knowledge, the “how to” guides that teach agents to use tools effectively. Skills are the brain of the agent. They turn tribal knowledge into portable, composable assets. But even skills are not enough. An agent with a hammer and a carpentry manual is still not a master carpenter.

Phase 3 is about context. This is where context graphs come in. A context graph is the accumulated record of every decision, every exception, and every outcome. It answers the question, “What happened last time?” It turns exceptions into precedents and tribal knowledge into institutional knowledge.

| Phase | Primitive | What It Provides | My Analogy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Tools (MCP) | Capability | The agent has a hammer. |

| Phase 2 | Skills (Agent Skills) | Expertise | The agent has a carpentry manual. |

| Phase 3 | Context (Context Graphs) | Experience | The agent has access to the record of every house it has ever built. |

The governance stack I have been advocating for (agent registries, tool registries, skill registries, policy engines) is the infrastructure that makes context graphs possible. The agent registry provides the identity of the agent making the decision. The tool registry (MCP) provides the capabilities available to that agent. The skill registry provides the expertise that guides the agent’s actions. And the orchestration layer is where the decision trace is captured and persisted.

Without this infrastructure, decision traces are ephemeral. They exist for a moment in the agent’s context window and then disappear. With this infrastructure, every decision becomes a durable artifact that can be audited, learned from, and used as precedent.

Gupta is right that agent first startups have a structural advantage here. They sit in the execution path. They see the full context at decision time. Incumbents, built on current state storage, simply cannot capture this.

But the bigger insight for me is this: we are not just building agents. We are building the decision record of the enterprise. The context graph is not a feature; it is the foundation of a new kind of system of record. The enterprises that win in the agentic era will be those that recognize this and invest in the infrastructure to capture, store, and leverage their decision traces.

We started by giving agents tools. Then we taught them skills. Now, we must give them context. That is the trillion dollar evolution.

References:

[1] Gupta, J. (2025, December 23). AI’s trillion dollar opportunity: Context graphs. X.

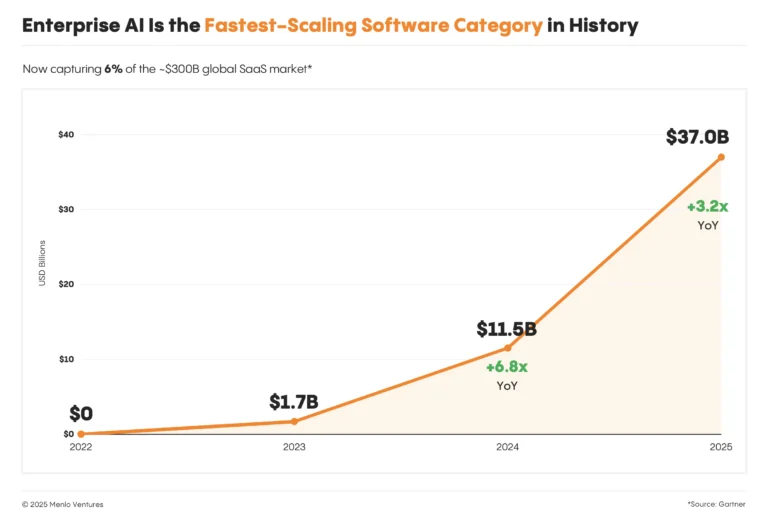

--- ## 2025: The Year Agentic AI Got Real (What Comes Next) URL: https://subramanya.ai/2025/12/23/2025-the-year-agentic-ai-got-real-and-what-comes-next/ Date: 2025-12-23 Tags: Agentic AI, Enterprise AI, MCP, Agent Skills, AI Agents, AI Infrastructure, Multi-Agent Systems, AI Governance, Open Standards, 2025 ReviewIf 2024 was the year of AI experimentation, 2025 was the year of industrialization. The speculative boom around generative AI has rapidly matured into the fastest-scaling software category in history, with autonomous agents moving from the lab to the core of enterprise operations. As we close out the year, it’s clear that the agentic AI landscape has been fundamentally reshaped by massive investment, critical standardization, and a clear-eyed focus on solving the hard problems of production readiness.

But this wasn’t just a story of adoption. 2025 was the year the industry confronted the architectural limitations of monolithic agents and began a decisive shift toward a more specialized, scalable, and governable future.

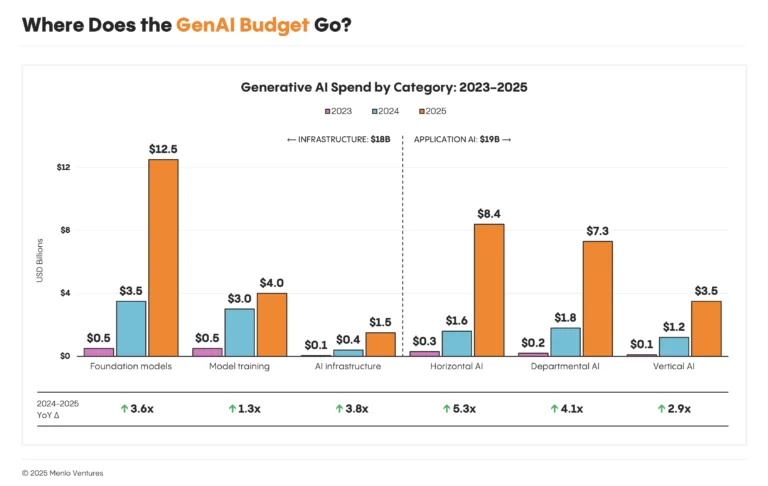

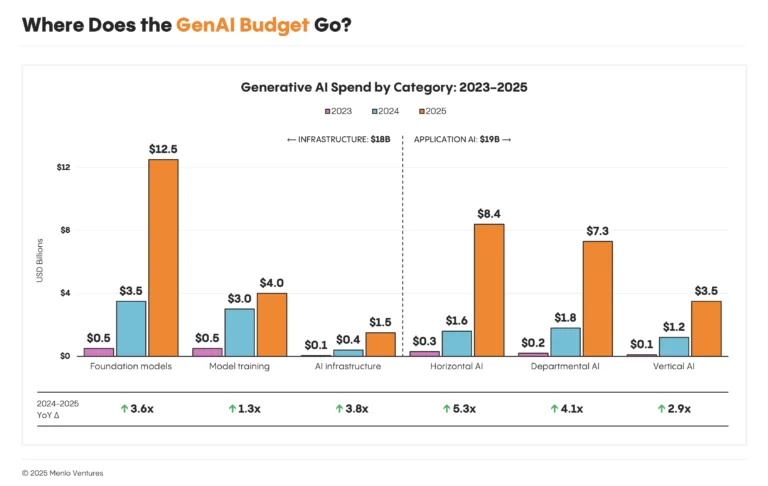

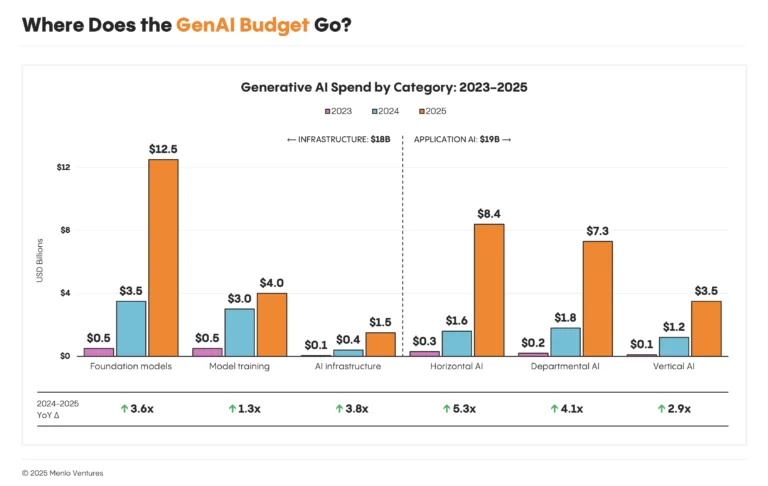

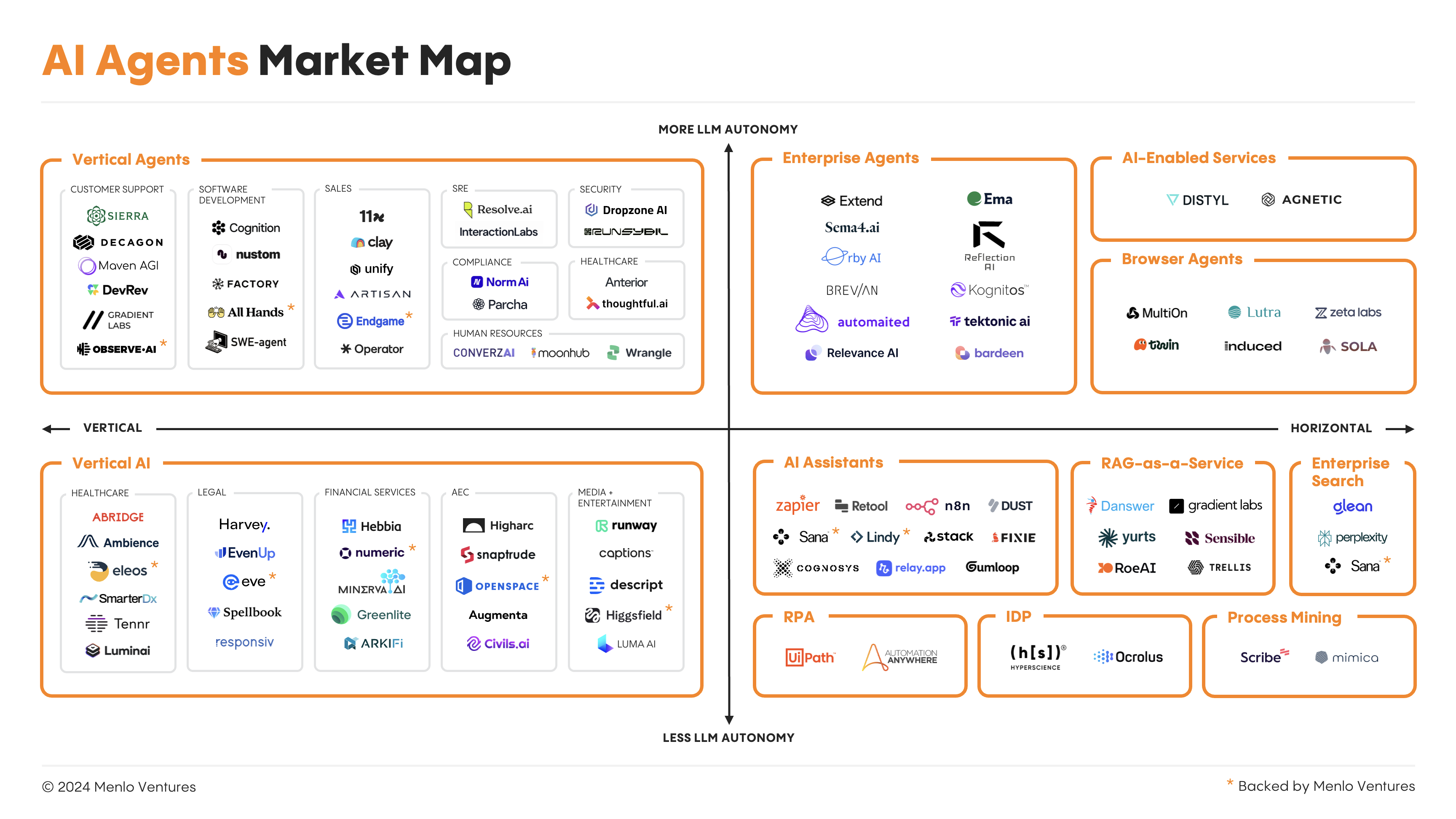

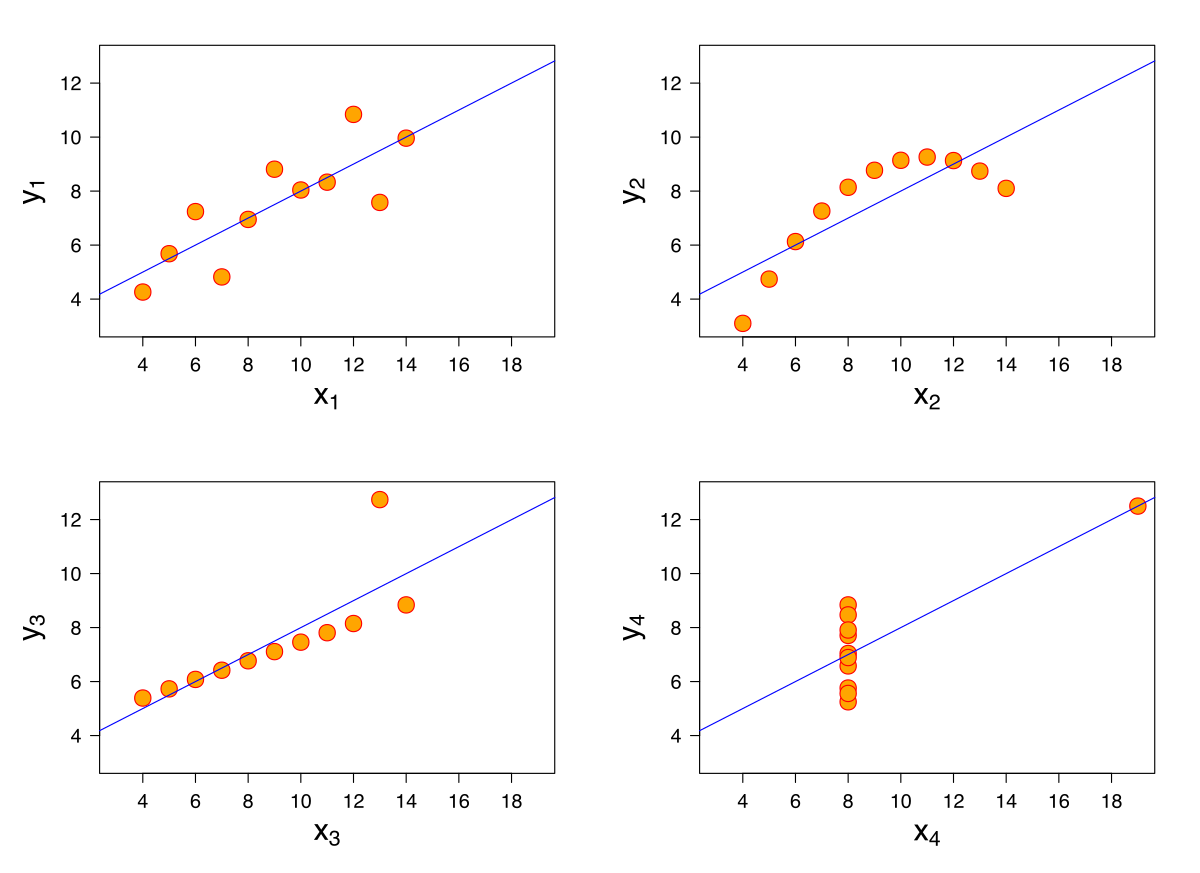

The most telling sign of this shift is the sheer volume of capital deployed. According to a December 2025 report from Menlo Ventures, enterprise spending on generative AI skyrocketed to $37 billion in 2025, a stunning 3.2x increase from the previous year [1]. This surge now accounts for over 6% of the entire global software market.

Crucially, over half of this spending ($19 billion) flowed directly into the application layer, demonstrating a clear enterprise priority for immediate productivity gains over long-term infrastructure bets. This investment is validated by strong adoption metrics, with a recent PwC survey finding that 79% of companies are already adopting AI agents [2].

Source: Menlo Ventures, 2025: The State of Generative AI in the Enterprise [1]

Source: Menlo Ventures, 2025: The State of Generative AI in the Enterprise [1]

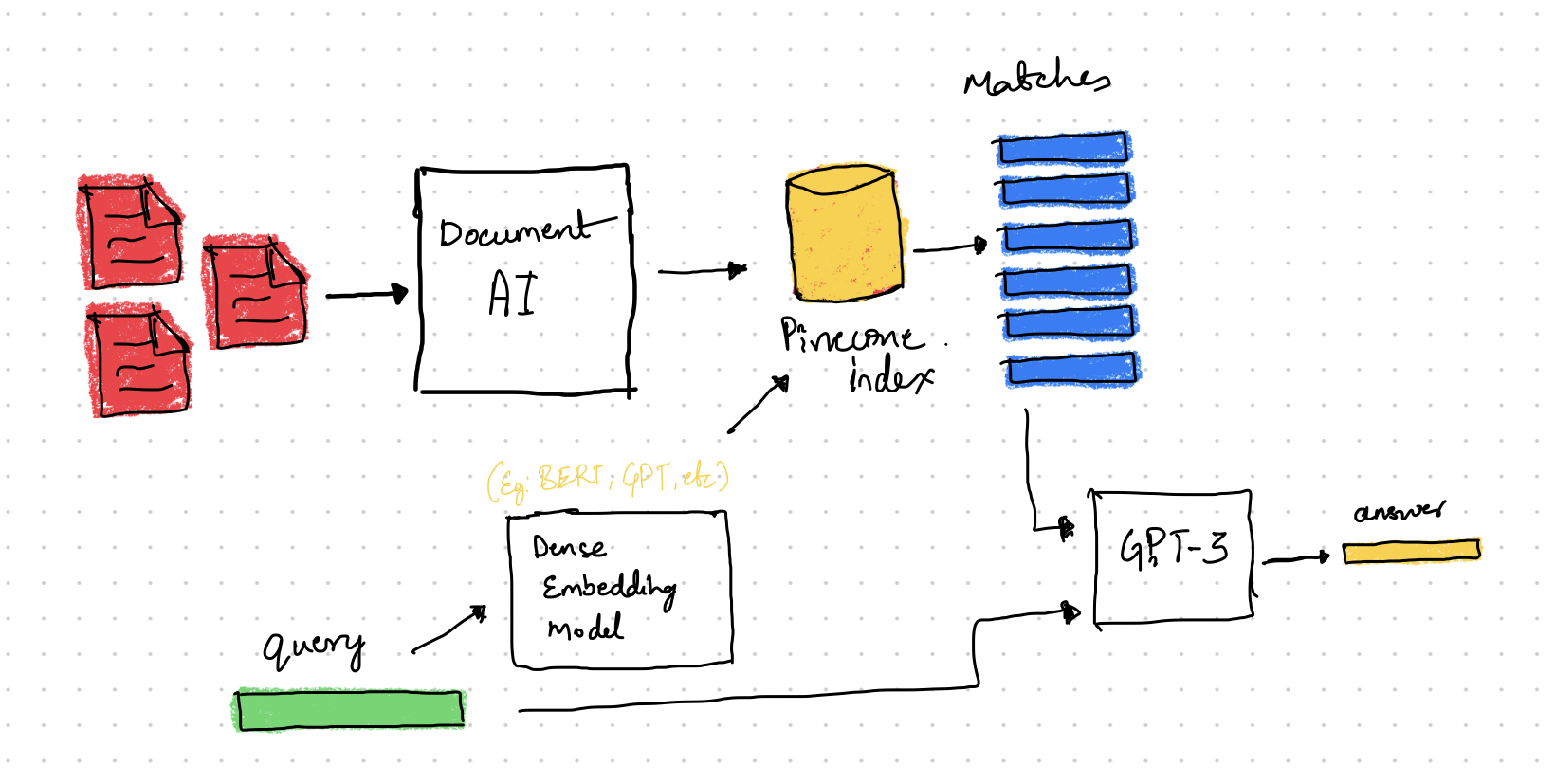

While the spending boom captured headlines, a quieter, more profound revolution was taking place in the infrastructure layer. The primary challenge addressed in 2025 was the interoperability crisis. The early agentic ecosystem was a chaotic landscape of proprietary APIs and fragmented toolsets, making it nearly impossible to build robust, cross-platform applications. This year, two key developments brought order to that chaos.

The Model Context Protocol (MCP), introduced in late 2024, became the de facto standard for agent-to-tool communication. Its first anniversary in November 2025 was marked by a major spec release that introduced critical enterprise features like asynchronous operations, server identity, and a formal extensions framework, directly addressing early complaints about its production readiness [3].

This culminated in the December 9th announcement that Anthropic, along with Block and OpenAI, was donating MCP to the newly formed Agentic AI Foundation (AAIF) under the Linux Foundation [4]. With over 10,000 active public MCP servers and 97 million monthly SDK downloads, MCP’s transition to a neutral, community-driven standard solidifies its role as the foundational protocol for the agentic economy.

The shift from fragmented, proprietary APIs to a unified, MCP-based approach simplifies agent-tool integration.

The shift from fragmented, proprietary APIs to a unified, MCP-based approach simplifies agent-tool integration.

Following the same playbook, Anthropic made another pivotal move on December 18th, opening up its Agent Skills specification [5]. This provides a standardized, portable way to equip agents with procedural knowledge, moving beyond simple tool-use to more complex, multi-step task execution. By making the specification and SDK available to all, the industry is fostering an ecosystem where skills can be developed, shared, and deployed across any compliant AI platform, preventing vendor lock-in.

These standardization efforts have unlocked the next major architectural shift: the move away from monolithic, general-purpose agents toward collections of specialized skills that function like a human team. No company hires a single “super-employee” to be a marketer, an engineer, and a financial analyst. They hire specialists who excel at their roles and collaborate to achieve a larger goal. The future of enterprise AI is the same.

This “multi-agent” or “skill-based” architecture is not just a theoretical concept. Anthropic’s own research showed that a multi-agent system—with a lead agent coordinating specialized sub-agents—outperformed a single, more powerful agent by over 90% on complex research tasks [6]. The reason is simple: specialization allows for greater accuracy, and parallelism allows for greater scale.

We are already seeing the first wave of companies built on this philosophy. YC-backed Getden.io, for example, provides a platform for non-engineers to build and collaborate with agents that can be composed of various skills and integrations [7]. This approach democratizes agent creation, allowing domain experts—not just developers—to build the specialized “digital employees” they need.

While 2025 solved the problem of connection, 2026 will be about solving the challenges of control and coordination at scale. As enterprises move from deploying dozens of agents to thousands of skills, a new set of problems comes into focus:

Governance at Scale: How do you manage access control, cost, and versioning for thousands of interconnected skills? The risk of “skill sprawl” and shadow AI is immense, demanding a new generation of governance platforms.

Reliability and Predictability: The non-deterministic nature of LLMs remains a major barrier to enterprise trust. For agents to run mission-critical processes, we need robust testing frameworks, better observability tools, and architectural patterns that ensure predictable outcomes.

Multi-Agent Orchestration: As skill-based systems become the norm, the primary challenge shifts from tool-use to agent coordination. How do you manage dependencies, resolve conflicts, and ensure a team of agents can reliably collaborate to complete a complex workflow? This is a frontier problem that will define the next generation of agentic platforms.

Security in a Composable World: A world of interoperable skills creates new attack surfaces. How do you secure the supply chain for third-party skills? How do you prevent a compromised agent from triggering a cascade of failures across a complex workflow? The security model for agentic AI is still in its infancy.

The groundwork laid in 2025 was monumental. It moved us from a world of isolated, experimental bots to the brink of a true agentic economy. But the journey is far from over. The companies that will win in 2026 and beyond will be those that master the art of building, managing, and securing not just agents, but entire workforces of specialized, collaborative skills.

References:

[2] PwC. (2025, May 16). PwC’s AI Agent Survey. PwC.

[6] Anthropic. (2025, June 13). How we built our multi-agent research system. Anthropic Engineering.

[7] Y Combinator. (2025). Den: Cursor for knowledge workers. Y Combinator.

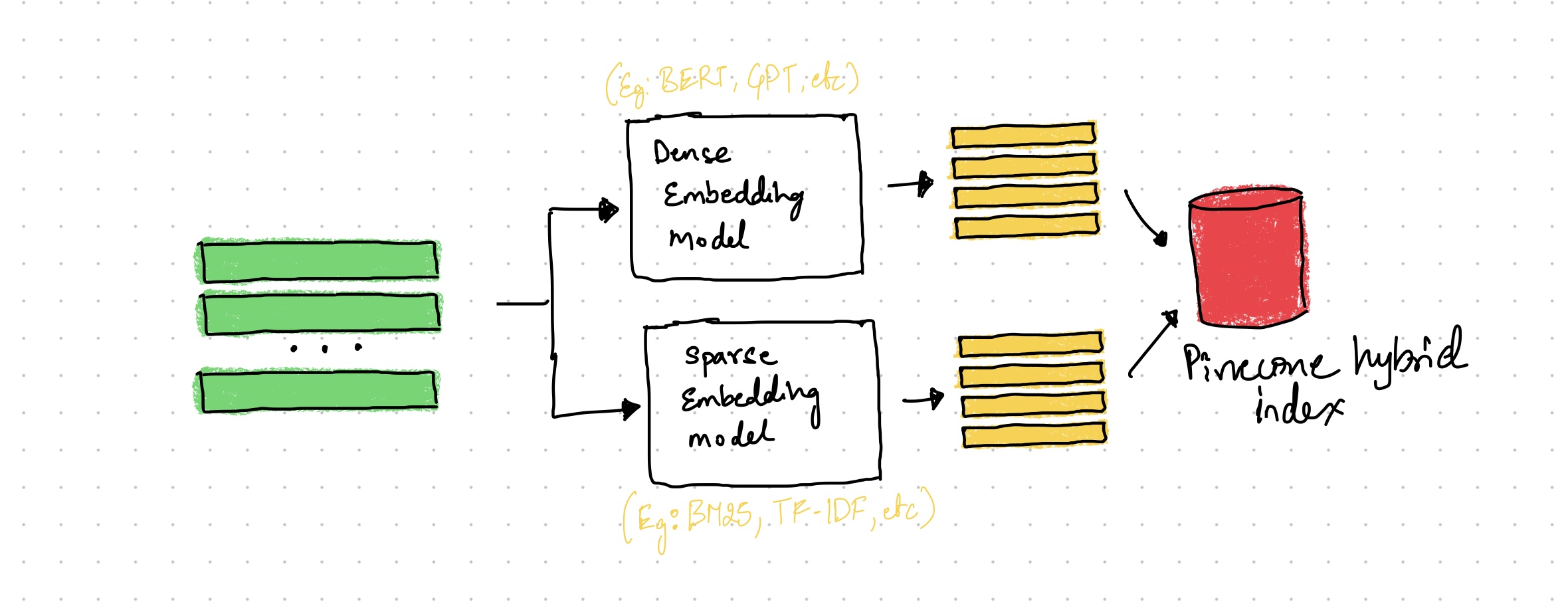

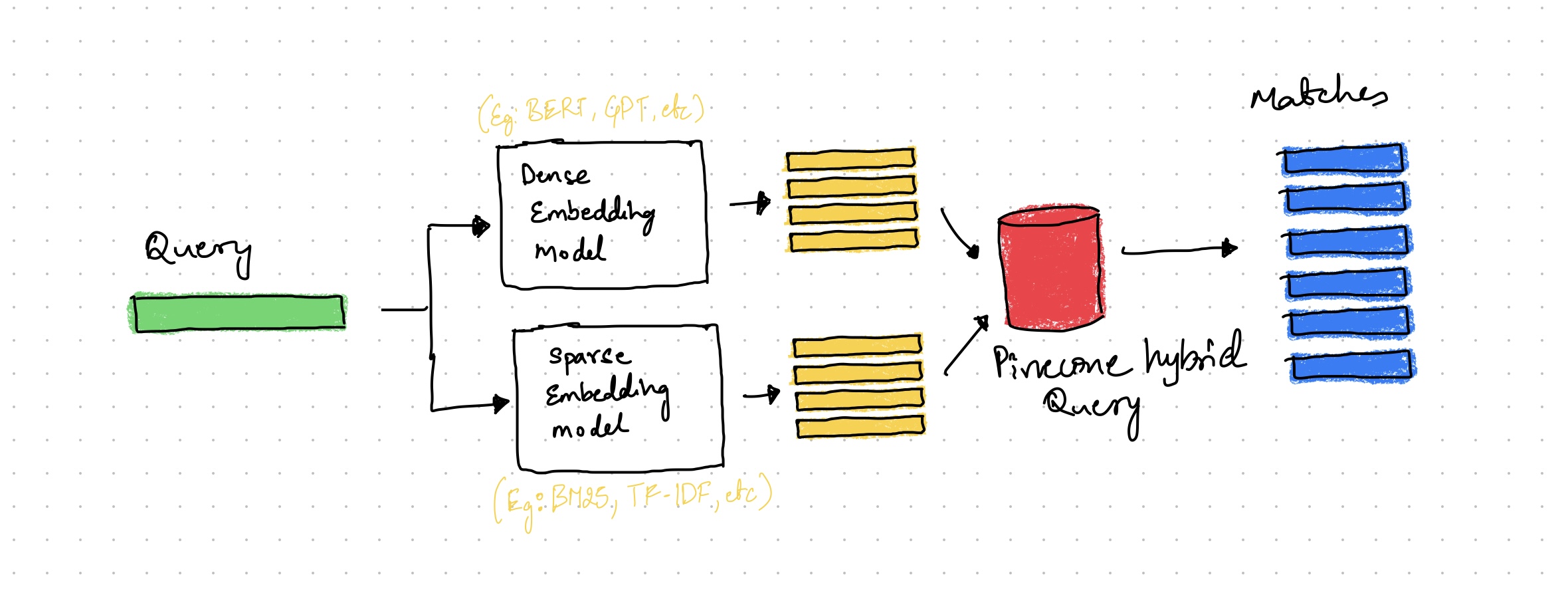

--- ## Agent Skills: The Missing Piece of the Enterprise AI Puzzle URL: https://subramanya.ai/2025/12/18/agent-skills-the-missing-piece-of-the-enterprise-ai-puzzle/ Date: 2025-12-18 Tags: AI Agents, Agent Skills, Enterprise AI, Anthropic, MCP, Agentic AI, AI Governance, Open Standards, AI Infrastructure, Agent ArchitectureThe enterprise AI landscape is at a critical juncture. We have powerful general-purpose models and a growing ecosystem of tools. But we are missing a crucial piece of the puzzle: a standardized, portable way to equip agents with the procedural knowledge and organizational context they need to perform real work. On December 18, 2025, Anthropic took a major step towards solving this problem by releasing Agent Skills as an open standard [1]. This move, following the same playbook that made the Model Context Protocol (MCP) an industry-wide success, is not just another feature release—it is a fundamental shift in how we will build and manage agentic workforces.

General-purpose agents like Claude are incredibly capable, but they lack the specialized expertise required for most enterprise tasks. As Anthropic puts it, “real work requires procedural knowledge and organizational context” [2]. An agent might know what a pull request is, but it doesn’t know your company’s specific code review process. It might understand financial concepts, but it doesn’t know your team’s quarterly reporting workflow. This gap between general intelligence and specialized execution is the primary barrier to scaling agentic AI in the enterprise.

Until now, the solution has been to build fragmented, custom-designed agents for each use case. This creates a landscape of “shadow AI”—siloed, unmanageable, and impossible to govern. What we need is a way to make expertise composable, portable, and discoverable. This is exactly what Agent Skills are designed to do.

At its core, an Agent Skill is a directory containing a SKILL.md file and optional subdirectories for scripts, references, and assets. It is, as Anthropic describes it, “an onboarding guide for a new hire” [2]. The SKILL.md file contains instructions, examples, and best practices that teach an agent how to perform a specific task. The key innovation is progressive disclosure, a three-level system for managing context efficiently:

name and description of each installed skill. This provides just enough information for the agent to know when a skill might be relevant, without flooding its context window.SKILL.md body. This gives the agent the core instructions it needs to perform the task.scripts/, references/, or assets/ directories. This allows skills to contain a virtually unbounded amount of context, loaded only as needed.This architecture is both simple and profound. It allows us to package complex procedural knowledge into a standardized, shareable format. It solves the context window problem by making context dynamic and on-demand. And by making it an open standard, Anthropic is ensuring that this expertise is portable across any compliant agent platform.

| Component | Purpose | Context Usage |

|---|---|---|

Metadata (name, description) |

Skill discovery | Minimal (loaded at startup) |

Instructions (SKILL.md body) |

Core task guidance | On-demand (loaded when skill is activated) |

Resources (scripts/, references/) |

Detailed context and tools | On-demand (loaded as needed) |

It is crucial to understand how Agent Skills relate to the Model Context Protocol (MCP). They are not competing standards; they are complementary layers of the agentic stack. As Simon Willison aptly puts it, “MCP provides the ‘plumbing’ for tool access, while agent skills provide the ‘brain’ or procedural memory for how to use those tools effectively” [3].

For example, MCP might give an agent access to a git tool. An Agent Skill would teach that agent your team’s specific git branching strategy, pull request template, and code review checklist. One provides the capability; the other provides the expertise. You need both to build a truly effective agentic workforce.

By releasing Agent Skills as an open standard, Anthropic is making a strategic bet on interoperability and ecosystem growth. This move has several critical implications for the enterprise:

The Agent Skills specification is, as Simon Willison notes, “deliciously tiny” and “quite heavily under-specified” [3]. This is a feature, not a bug. It provides a flexible foundation that the community can build upon. We can expect to see the specification evolve as it is adopted by more platforms and as best practices emerge.

However, the power of skills—especially their ability to execute code—also introduces new governance challenges. Organizations will need to establish clear processes for auditing, testing, and deploying skills from trusted sources. We will need skill registries to manage the discovery and distribution of skills, and policy engines to control which agents can use which skills in which contexts. These are the next frontiers in agentic infrastructure.

Agent Skills are not just a new feature; they are a new architectural primitive for the agentic era. They provide the missing link between general intelligence and specialized execution. By making expertise composable, portable, and standardized, Agent Skills will unlock the next wave of innovation in enterprise AI. The race is no longer just about building the most powerful models; it is about building the most capable and knowledgeable agentic workforce.

References:

[1] Anthropic. (2025, December 18). Agent Skills. Agent Skills.

[3] Willison, S. (2025, December 19). Agent Skills. Simon Willison’s Weblog.

--- ## From Boom to Build-Out: The State of Enterprise AI in 2026 URL: https://subramanya.ai/2025/12/10/from-boom-to-build-out-the-state-of-enterprise-ai-in-2026/ Date: 2025-12-10 Tags: Enterprise AI, AI Agents, Agentic Workflows, AI Adoption, Platform Strategy, Developer Tools, AI Infrastructure, Generative AI, Enterprise SoftwareThe era of AI experimentation is over. What began as a speculative boom has rapidly industrialized into the fastest-scaling software category in history. According to a new report from Menlo Ventures, enterprise spending on generative AI skyrocketed to $37 billion in 2025, a stunning 3.2x increase from the previous year [3]. This isn’t just hype; it’s a fundamental market shift. AI now commands 6% of the entire global SaaS market—a milestone reached in just three years [3].

This explosive growth signals a new phase of enterprise adoption. The conversation has moved beyond simple chatbots and one-off tasks to focus on building durable, agentic infrastructure. Reports from OpenAI, Anthropic, and Menlo Ventures all point to the same conclusion: the battleground for competitive advantage has shifted from model performance to platform execution.

So, where is this money going? Over half of all enterprise AI spend $19 billion is flowing directly into the application layer [3]. This indicates a clear preference for immediate productivity gains over long-term, in-house infrastructure projects. The “buy vs. build” debate has decisively tilted towards buying, with 76% of AI use cases now being purchased from vendors, a dramatic reversal from 2024 when the split was nearly even [3].

This trend is fueled by two factors: AI solutions are converting at nearly double the rate of traditional SaaS (47% vs. 25%), and product-led growth (PLG) is driving adoption at 4x the rate of traditional software [3]. Individual employees and teams are adopting AI tools, proving their value, and creating a powerful bottom-up flywheel that short-circuits legacy procurement cycles.

This rapid adoption is not just about doing old tasks faster; it’s about enabling entirely new ways of working. The data shows a clear architectural shift from simple, conversational queries to structured, agentic workflows that are deeply embedded in core business processes.

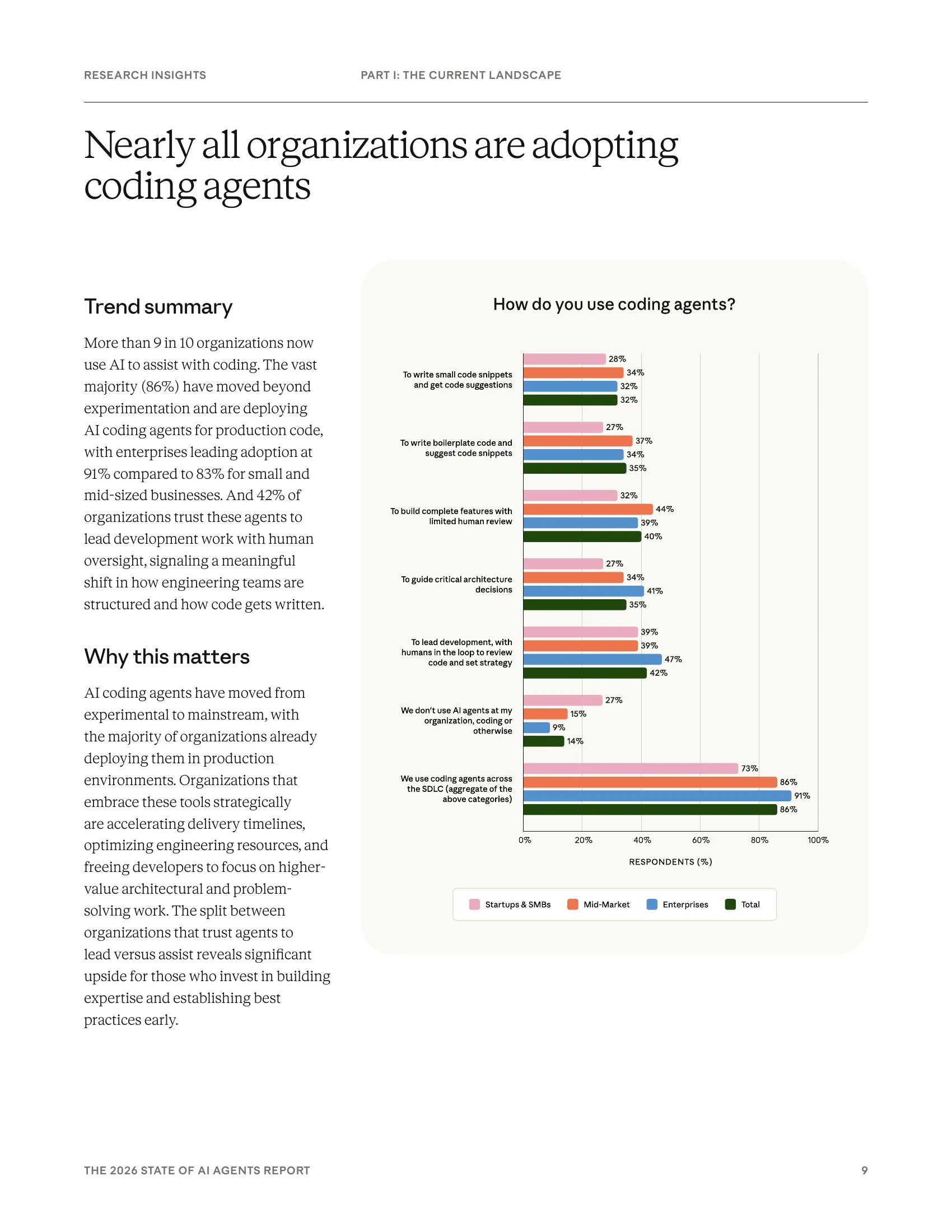

Anthropic’s 2026 survey reveals that 57% of organizations are already deploying agents for multi-stage processes, with 81% planning to tackle even more complex, cross-functional workflows in the coming year [1]. This transition from single-turn interactions to persistent, multi-step agents is where true business transformation is happening.

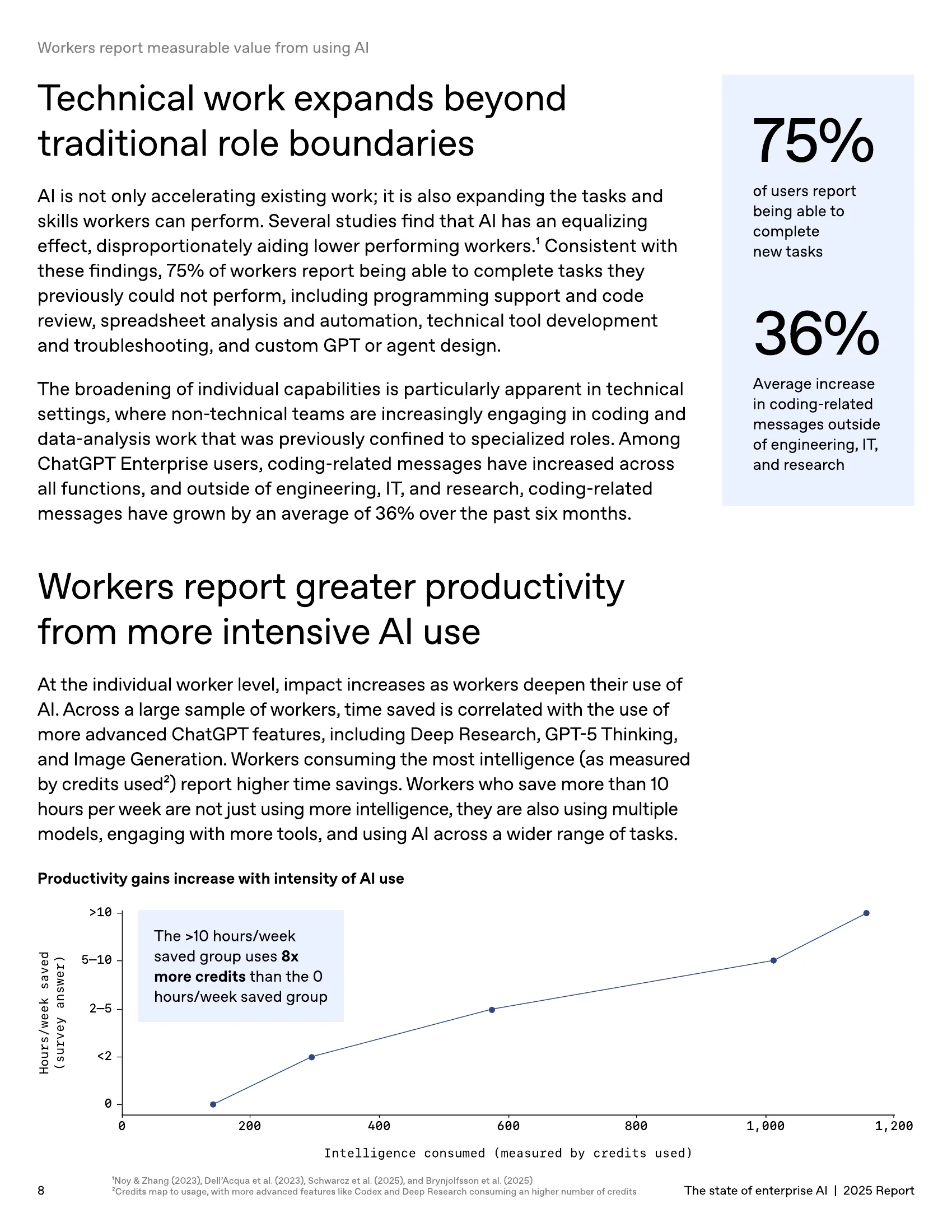

OpenAI’s 2025 report highlights a 19x year-to-date increase in the use of structured workflows like Custom GPTs and Projects, with 20% of all enterprise messages now being processed through these repeatable systems [2]. The impact is tangible, with 80% of organizations reporting measurable ROI on their agent investments and workers saving an average of 40-60 minutes per day [1, 2].

Perhaps most striking is that 75% of workers report being able to complete tasks they previously could not perform, including programming support, spreadsheet analysis, and technical tool development [2]. This democratization of technical capabilities is fundamentally reshaping how work gets done.

Nearly all organizations (90%) now use AI to assist with development, and 86% deploy agents for production code [1]. The adoption is so pervasive that coding-related messages have increased by 36% even among non-technical workers [2].

Organizations report time savings across the entire development lifecycle: planning and ideation (58%), code generation (59%), documentation (59%), and code review and testing (59%) [1]. This systematic integration across the full software development lifecycle is accelerating delivery timelines and freeing developers to focus on higher-value architectural and problem-solving work.

As AI becomes an essential, intelligent layer of the enterprise tech stack, the primary barriers to scaling are no longer model capabilities but organizational and architectural readiness. The top challenges cited by leaders are integration with existing systems (46%), data access and quality (42%), and change management (39%) [1]. These are not model problems; they are platform problems.

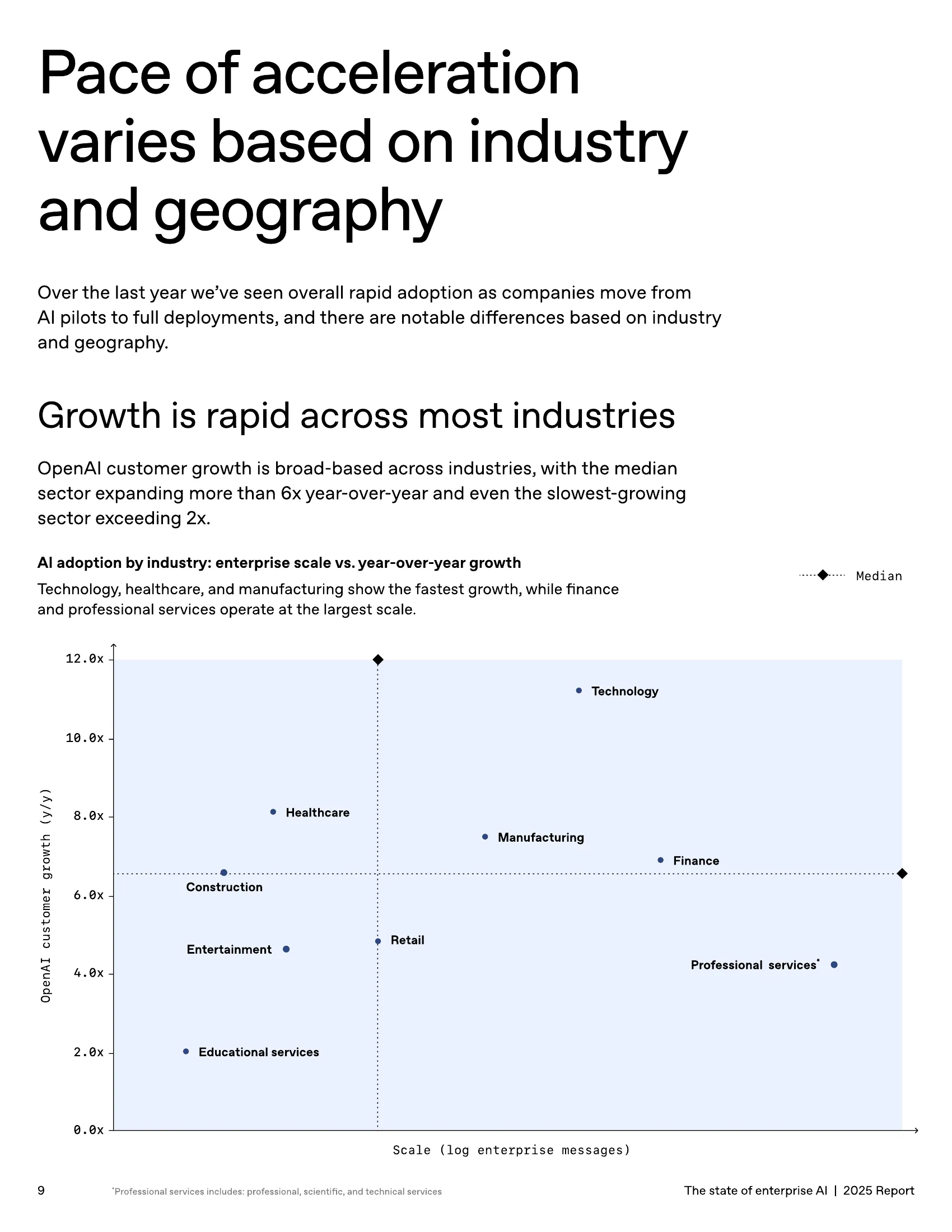

This new reality is creating a widening performance gap. OpenAI’s data shows that “frontier firms” that treat AI as integrated infrastructure see 2x more engagement per seat, and their workers are 6x more active than the median [2]. Technology, healthcare, and manufacturing are seeing the fastest growth (11x, 8x, and 7x respectively), while professional services and finance operate at the largest scale [2].

The state of enterprise AI in 2026 is clear: the gold rush is over, and the era of building the railroads has begun. Success is no longer defined by having the best model, but by having the best platform to deploy, manage, and secure intelligence at scale.

References:

[1] Anthropic. (2025). The 2026 State of AI Agents Report. Anthropic.

[2] OpenAI. (2025). The state of enterprise AI 2025 report. OpenAI.

--- ## The Three-Platform Problem in Enterprise AI URL: https://subramanya.ai/2025/12/07/the-three-platform-problem-in-enterprise-ai/ Date: 2025-12-07 Tags: AI Platform, Enterprise AI, Low-Code, DevOps, Platform Architecture, API-First, Infrastructure, Developer Tools, Platform StrategyEnterprise AI has a platform problem. The tools to build AI-powered applications exist, but they’re scattered across three disconnected ecosystems—each solving part of the puzzle, none providing a complete solution.

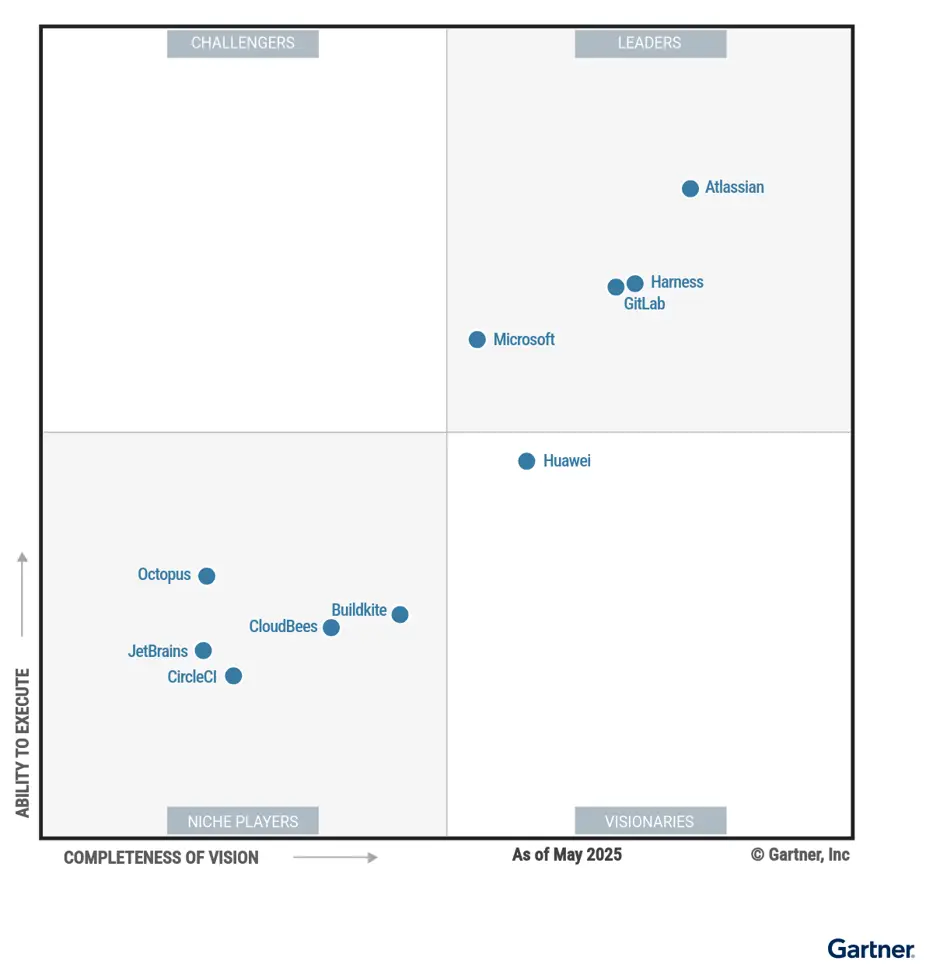

This isn’t a “too many choices” problem. It’s an architectural one. Gartner tracks these ecosystems in separate Magic Quadrants because they serve fundamentally different users with different needs. But building production AI applications requires capabilities from all three.

Platforms like Microsoft Power Apps, Mendix, and OutSystems let business users build applications quickly without writing code. They excel at UI, rapid prototyping, and workflow automation.

Gartner Magic Quadrant for Enterprise Low-Code Application Platforms

Gartner Magic Quadrant for Enterprise Low-Code Application Platforms

What they do well: Speed to prototype, accessibility for non-developers, business process automation.

What they lack: Infrastructure control, enterprise governance at scale, and the flexibility professional developers need.

GitLab, Microsoft Azure DevOps, and Atlassian provide CI/CD pipelines, source control, and deployment infrastructure. They answer the “how do we ship and operate this reliably?” question.

Gartner Magic Quadrant for DevOps Platforms

Gartner Magic Quadrant for DevOps Platforms

What they do well: Security, governance, testing, deployment automation, operational excellence.

What they lack: They don’t help you build faster—they help you ship what you’ve already built.

Cloud providers (AWS, GCP, Azure) and specialized vendors offer models, MLOps tooling, and inference infrastructure. They provide the intelligence layer.

Gartner Magic Quadrant for AI Code Assistants

Gartner Magic Quadrant for AI Code Assistants

What they do well: Model access, training infrastructure, inference at scale.

What they lack: An opinion on how you actually build and deploy applications around those models.

When your AI strategy requires stitching together leaders from three separate ecosystems, you pay an integration tax:

Workflow disconnects. A business user prototypes an AI workflow in a low-code tool. A developer rebuilds it from scratch to meet security requirements. The prototype and production system share nothing but a spec document.

Observability gaps. Tracing a user request through a low-code UI, into a DevOps pipeline, through an AI model call, and back is nearly impossible without custom instrumentation.

Governance drift. Security policies enforced in your DevOps platform don’t automatically apply to your low-code environment. Compliance becomes a manual audit.

Your most capable engineers end up writing glue code instead of building products.

The solution isn’t better integrations—it’s platforms built on a different architecture.

Replit offers a useful case study. They’ve grown from $10M to $100M ARR in under six months by building a platform where:

The same infrastructure serves both citizen developers and professionals. A business user building through natural language (“create a customer feedback dashboard”) and a developer writing code are using the same underlying APIs, the same deployment system, the same security model.

AI is native, not bolted on. Their Agent can build, test, and deploy complete applications autonomously—but it’s using the same environment a professional developer would use. No “export to production” step.

Governance applies universally. Database access, API key management, and deployment policies are platform-level concerns. They apply whether you’re prompting an AI agent or writing TypeScript.

This is the “headless-first” pattern that companies like Stripe and Twilio proved out: build the API, make it excellent, then layer interfaces on top. The UI for non-developers and the API for developers are just different clients to the same system.

If you’re evaluating AI platforms, the question isn’t “which low-code tool, which DevOps platform, and which AI vendor?”

The better question: Does this platform unify these concerns, or will we be writing integration code for the next three years?

Look for:

API-first architecture. Can professional developers access everything through APIs? Is the UI built on those same APIs?

Built-in deployment and operations. Does prototyping in the platform give you production-ready infrastructure, or does it give you an export button and a prayer?

Platform-level governance. Are security, compliance, and cost controls configured once and inherited everywhere, or are they per-tool?

The platforms winning in this space aren’t the ones with the longest feature lists. They’re the ones that recognized the three-ecosystem problem and architected around it from day one.

--- ## The Platform Convergence: Why the Future of AI SaaS is Headless-First URL: https://subramanya.ai/2025/12/02/the-platform-convergence-why-the-future-of-ai-saas-is-headless-first/ Date: 2025-12-02 Tags: AI Platform, Agentic AI, Enterprise AI, AI Gateway, Agent Builder, Developer Tools, Infrastructure, Platform Architecture, Headless Architecture, AI SaaSThe AI agent market is experiencing its own big bang—but this rapid expansion is creating fundamental fragmentation. Enterprises deploying agents at scale are caught between two incomplete solutions: Agent Builders and AI Gateways.

Agent Builders democratize creation through no-code interfaces. AI Gateways provide enterprise governance over costs, security, and compliance. Both are critical, but in their current separate forms, they force a false choice: speed or control? The reality is, you need both.

We’ve seen this movie before. The most successful developer platforms—Stripe, Twilio, Shopify—aren’t just slick UIs or robust infrastructure. They are headless-first platforms that masterfully combine both.

Stripe didn’t win payments by offering a payment form. Twilio didn’t win communications by providing a dashboard. They won by providing a powerful, programmable foundation with APIs as the primary interface. Their UIs are built on the same public APIs their customers use. Everything is composable, programmable, and extensible.

| Principle | Benefit |

|---|---|

| API-First Design | Platform’s own UI uses public APIs, ensuring completeness |

| Progressive Complexity | Start with no-code UI, graduate to API without migration |

| Composability | Every capability is a building block for higher-level abstractions |

| Extensibility | Third parties build on the platform, creating ecosystem effects |

This is the blueprint for AI platforms: not just a UI for building agents, nor just a gateway for traffic—but a comprehensive, programmable platform for building, running, and governing AI at every layer.

Agent Builders (Microsoft Copilot Studio, Google Agent Builder) empower non-technical users to create agents in minutes. The problem arises at scale: Who manages API keys? Who tracks costs? Who ensures compliance? This democratization often creates ungoverned “shadow IT”—business units spinning up agents independently, each with its own credentials and error handling. Platform teams discover the proliferation only when something breaks.

AI Gateways (Kong, Apigee) solve the governance problem with centralized security, cost monitoring, and compliance. But a gateway is just plumbing—it doesn’t accelerate creation. Business users wait in IT queues while engineers build what they need. Innovation slows to a crawl.

Integrating both categories creates its own integration tax: two authentication systems, two deployment processes, broken observability across disconnected logs, and policy enforcement gaps where builder retry logic conflicts with gateway rate limits.

The solution is a unified, headless-first platform with four integrated layers:

Layer 1: UI Layer — Intuitive no-code agent builder for business users, built on top of the platform’s own APIs. Natural language definition, visual workflow design, one-click deployment with inherited governance.

Layer 2: Runtime Layer — Enterprise-grade gateway that every agent runs through automatically. Centralized auth (OAuth, OIDC, SAML), real-time policy enforcement, distributed tracing, cost tracking, anomaly detection.

Layer 3: Platform Layer — Comprehensive APIs and SDKs for developers. REST/GraphQL endpoints, language-specific SDKs, agent lifecycle management, webhook system for event-driven architectures.

Layer 4: Ecosystem Layer — Marketplace for discovering and sharing agents, tools, and integrations. Internal registry, reusable components, version control, usage analytics.

The difference between fragmented and unified approaches:

| Capability | Fragmented Tools | Unified Platform |

|---|---|---|

| Agent Creation | Separate builder | Integrated no-code + API/SDK |

| Infrastructure | Separate gateway | Built-in gateway with inherited policies |

| Observability | Disconnected logs | End-to-end unified tracing |

| Policy Management | Manual coordination | Single policy engine |

| Developer Experience | High friction | Single, cohesive API surface |

| Audit & Compliance | Cross-system correlation | Native audit trails |

With a unified platform: business user creates agent in UI → platform applies policies automatically → agent deploys with full observability → platform team monitors centrally → developer extends via API without migration.

Self-Service AI: HR builds a resume screening agent in 20 minutes. It inherits security policies automatically. Cost allocates to HR’s budget. Compliance trail generates without extra work.

AI-Powered Products: Engineers embed agent capabilities into customer-facing apps using platform APIs. Multi-tenant isolation, usage-based billing, and governance come built-in.

Internal Marketplace: Marketing’s “competitive intelligence” agent gets discovered by Sales. One-click deployment. Usage metrics show ROI across the organization.

The debate over agent builder vs. AI gateway is a red herring—a false choice leading to fragmented, expensive solutions. The real question: point solution or true platform?

In payments, Stripe won by unifying developer APIs with merchant tools. In communications, Twilio won by combining carrier control with developer speed. The AI platform market is at the same inflection point.

The future isn’t about stitching tools together; it’s about building on a unified, programmable foundation. The organizations that invest in platform-first infrastructure—rather than cobbling together point solutions—will move faster, govern more effectively, and build more sophisticated agentic systems.

The convergence is coming. The question is whether you’ll be ahead of it or behind it.

--- ## MCP Enterprise Readiness: How the 2025-11-25 Spec Closes the Production Gap URL: https://subramanya.ai/2025/12/01/mcp-enterprise-readiness-how-the-2025-11-25-spec-closes-the-production-gap/ Date: 2025-12-01 Tags: MCP, Enterprise AI, Agentic AI, Security, OAuth, Authentication, Infrastructure, Agent Ops, Governance, Enterprise IntegrationJust over a week ago, the Model Context Protocol celebrated its first anniversary with the release of the 2025-11-25 specification [1]. The announcement was rightly triumphant—MCP has evolved from an experimental open-source project to a foundational standard backed by GitHub, OpenAI, Microsoft, and Block, with thousands of active servers in production [1].

But beneath the celebration lies a more interesting story: this spec release is not just an evolution; it’s a strategic pivot toward enterprise readiness. For the past year, MCP has succeeded as a developer tool—a convenient way to connect AI models to data and capabilities during experimentation. The 2025-11-25 spec is different. It introduces features explicitly designed to solve the operational, security, and governance challenges that prevent organizations from deploying agent-tool ecosystems at enterprise scale.

This article examines three key features from the new spec and analyzes how they close what I call the “production gap”—the distance between experimental agent prototypes and enterprise-grade agentic infrastructure.

Before diving into the technical features, we need to understand the problem they’re solving. Organizations have been experimenting with MCP-powered agents for months, often with impressive results in controlled environments. Yet most of these projects remain trapped in pilot purgatory, unable to progress to production deployments. The barriers are not technical whimsy; they are fundamental operational requirements:

| Requirement | Why It Matters | What’s Been Missing |

|---|---|---|

| Asynchronous Operations | Real-world tasks like report generation, data analysis, and workflow automation can take minutes or hours, not milliseconds. | MCP connections are synchronous. Long-running tasks force clients to hold connections open or build custom polling systems. |

| Enterprise Authentication | Organizations need centralized control over which users, agents, and services can access sensitive tools and data. | The original OAuth flow assumed a consumer app model. It lacked support for machine-to-machine auth and didn’t integrate with enterprise Identity Providers. |

| Extensibility | Different industries and use cases require custom capabilities without fragmenting the core protocol. | There was no formal mechanism to standardize extensions, leading to proprietary, incompatible implementations. |

These aren’t edge cases; they are the table stakes for production systems. The 2025-11-25 spec directly addresses each one.

Perhaps the most transformative addition is the new Tasks primitive [2]. While still marked as experimental, it fundamentally changes how agents interact with MCP servers for long-running operations.

Traditional MCP follows the classic RPC pattern: the client sends a request, the server processes it, and the server returns a response—all within a single connection. This works beautifully for quick operations like reading a database row or checking a weather API. But it breaks down for realistic enterprise workflows:

Organizations have been forced to build custom workarounds: job queues, polling systems, callback webhooks—all non-standard, all increasing complexity and reducing interoperability.

The new Tasks feature introduces a standard “call-now, fetch-later” pattern:

task hint.taskId.working, completed, failed) using standard Task operations.taskId.This is more than syntactic sugar. It provides a uniform abstraction for asynchronous work across the entire MCP ecosystem. An agent framework doesn’t need to know whether it’s calling a data pipeline, a deployment system, or a document processor—the async pattern is the same.

In production environments, this changes everything. An AI assistant orchestrating a complex workflow can:

This is how real autonomous agents operate. The Tasks primitive makes it possible within a standard, interoperable protocol.

The original MCP spec included OAuth 2.0 support, but it was modeled on consumer app patterns (think “Log in with GitHub”). That model doesn’t work for enterprise use cases, where organizations need centralized identity management, audit trails, and policy-based access control. The 2025-11-25 spec introduces two critical updates to close this gap.

The first change is replacing Dynamic Client Registration (DCR) with Client ID Metadata Documents (CIMD) [3]. In the old model, every MCP client had to register with every authorization server it wanted to use—a scalability nightmare in federated enterprise environments.

With CIMD, the client_id is now a URL that the client controls (e.g., https://agents.mycompany.com/sales-assistant). When an authorization server needs information about this client, it fetches a JSON metadata document from that URL. This document includes:

This approach creates a decentralized trust model anchored in DNS and HTTPS. The authorization server doesn’t need a pre-existing relationship with the client; it trusts the metadata published at the URL. For large organizations with dozens of agent applications and multiple MCP providers, this dramatically reduces operational overhead.

The second critical addition is support for the OAuth 2.0 client_credentials flow via the M2M OAuth extension. This enables machine-to-machine authentication—allowing agents and services to authenticate directly with MCP servers without a human user in the loop.

Why does this matter? Consider these enterprise scenarios:

None of these involve an interactive user. They are autonomous services that need persistent, secure credentials to access tools on behalf of the organization. The client_credentials flow is the standard OAuth mechanism for exactly this use case, and its inclusion in MCP makes headless agentic systems viable.

Perhaps the most strategically significant feature for large enterprises is the Cross App Access (XAA) extension. This solves a governance problem that has plagued the consumerization of enterprise AI: uncontrolled tool sprawl.

In the standard OAuth flow, a user grants consent directly to an AI application to access a tool. The enterprise Identity Provider (IdP) sees only that “Alice logged in to the AI app,” not that “Alice’s AI agent is now accessing the payroll system.” This creates a governance black hole.

XAA changes the authorization flow to insert the enterprise IdP as a central policy enforcement point. Now, when an agent attempts to access an MCP server:

This provides centralized visibility and control over the entire agent-tool ecosystem. Security teams can monitor which agents are accessing which tools, set organization-wide policies (e.g., “no agents can access PII without human review”), and audit all delegated access. It eliminates shadow AI and provides the compliance story that regulated industries demand.

Together, these OAuth enhancements transform MCP from a developer convenience into a governed, auditable integration layer. Organizations can:

The third major addition is the introduction of a formal Extensions framework [3]. This is a governance mechanism for the protocol itself, allowing the community to develop new capabilities without fragmenting the ecosystem.

Every successful protocol faces this dilemma: enable innovation fast enough to keep up with evolving use cases, but standardize carefully enough to maintain interoperability. Move too slowly, and the community builds proprietary extensions that fragment the ecosystem. Move too quickly, and the core protocol becomes bloated with niche features that most implementations don’t need.

MCP’s solution is a structured extension process. New capabilities are proposed as Specification Enhancement Proposals (SEPs), which undergo community review and can be adopted incrementally. Extensions are namespaced and clearly marked, so implementations can selectively support them without breaking compatibility.

For enterprises, this is critical. Different industries have unique requirements:

The formal extensions framework allows organizations to develop these capabilities as standard, interoperable extensions rather than proprietary forks. This preserves the core value proposition of MCP—a universal protocol for agent-tool communication—while enabling the customization required for production use.

One more feature deserves mention: Sampling with Tools [3]. This allows MCP servers themselves to act as agentic systems, capable of multi-step reasoning and tool use. A server can now request the client to invoke an LLM on its behalf, enabling server-side agents.

Why is this powerful? It enables compositional agent architectures. A high-level agent can delegate to specialized MCP servers, which themselves use agentic reasoning to fulfill complex requests. For example:

This nested, hierarchical approach is how real autonomous systems will scale. By making it a standard protocol feature rather than a custom implementation, MCP provides the foundation for a rich ecosystem of specialized, composable agents.

The 2025-11-25 MCP specification is not a radical redesign; it’s a targeted set of enhancements that directly address the barriers preventing enterprise adoption. By introducing:

the spec closes the production gap—the distance between experimental prototypes and scalable, secure, enterprise-grade systems.

This is the moment when MCP transitions from a promising developer tool to a foundational piece of enterprise infrastructure. Organizations that have been waiting for “production readiness” signals now have them. The features are there. The governance mechanisms are there. The security model is there.

The next phase of agentic AI will be defined not by flashy demos, but by the quiet, reliable, at-scale operation of autonomous systems integrated deeply into enterprise workflows. The 2025-11-25 MCP spec is the technical foundation that makes this future possible.

For technology leaders evaluating whether to invest in MCP-based infrastructure, the calculus has changed. This is no longer an experimental protocol; it’s a production standard. The organizations that adopt it now, build their agent ecosystems on it, and contribute to its continued evolution will define the next decade of enterprise AI.

References:

[2] Model Context Protocol. (2025, November 25). Tasks. Model Context Protocol Specification.

--- ## The Governance Stack: Operationalizing AI Agent Governance at Enterprise Scale URL: https://subramanya.ai/2025/11/20/the-governance-stack-operationalizing-ai-agent-governance-at-enterprise-scale/ Date: 2025-11-20 Tags: AI, Agents, Agentic AI, Governance, Enterprise AI, Agent Ops, MCP, Security, Infrastructure, Compliance, AI ManagementEnterprise adoption of AI agents has reached a tipping point. According to McKinsey’s 2025 global survey, 88% of organizations now report regular use of AI agents in at least one business function, with 62% actively experimenting with agentic systems [1]. Yet this rapid adoption has created a critical disconnect: while organizations understand the importance of governance, they struggle with the implementation of it. The same survey reveals that 40% of technology executives believe their current governance programs are insufficient for the scale and complexity of their agentic workforce [1, 2].

The problem is not a lack of frameworks. Numerous organizations have published comprehensive governance principles—from Databricks’ AI Governance Framework to the EU AI Act’s regulatory requirements [2]. The problem is that governance has remained largely conceptual, living in policy documents and compliance checklists rather than in the operational infrastructure where agents actually execute.

This article presents the technical foundation required to operationalize governance at scale: the Governance Stack. This is the integrated set of platforms, protocols, and enforcement mechanisms that transform governance from aspiration into automated reality across the entire agentic workforce lifecycle.

Traditional enterprise governance models were designed for static systems and predictable workflows. An application goes through a review process, gets deployed, and then operates within well-defined boundaries. Governance checkpoints are discrete events: code reviews, security scans, compliance audits.

Agentic AI shatters this model. Agents are dynamic, adaptive systems that make autonomous decisions, spawn sub-agents, and interact with constantly evolving toolsets. They don’t follow predetermined paths; they reason, plan, and execute based on context. As one industry analysis puts it, the governance question shifts from “did the code do what we programmed?” to “did the agent make the right decision given the circumstances?” [3].

This creates four fundamental challenges that traditional governance infrastructure cannot address:

| Challenge | Traditional Governance | Agentic Reality |

|---|---|---|

| Decision-Making | Predetermined logic paths, testable and auditable | Context-dependent reasoning, emergent behavior |

| Delegation | Single service boundary, clear ownership | Recursive agent chains, distributed responsibility |

| Policy Enforcement | Deployment-time checks, periodic audits | Real-time enforcement at the moment of action |

| Auditability | Static code and logs | Dynamic decision traces across multiple agents and tools |

The governance gap is the distance between what existing frameworks prescribe and what existing infrastructure can enforce. Closing this gap requires purpose-built technology.

Drawing on the foundational pillars outlined in frameworks like Databricks’ AI Governance model [2], we can define a technical architecture—a Governance Stack—that provides the infrastructure necessary to operationalize these principles. This stack has five integrated layers, each addressing a specific aspect of agent lifecycle management.

Before governance can be enforced, we must know who (or what) is making a request. This requires a robust identity layer specifically designed for autonomous agents, not just human users.

As discussed in previous work on OIDC-A (OpenID Connect for Agents), this layer provides [4]:

This identity foundation is the prerequisite for all subsequent layers. Without it, governance policies have no subject to act upon.

Governance requires visibility. The second layer of the stack is a comprehensive registry system that provides a single source of truth for:

As explored in our previous article on private registries, this layer transforms governance from a manual audit process into an automated, enforceable function of the infrastructure itself [5]. Agents that aren’t registered can’t deploy. Tools that haven’t been vetted can’t be accessed.

The third layer is where governance rules are codified and enforced in real-time. This includes:

Agent Firewalls and MCP Gateways: Acting as intermediaries between agents and their tools, these gateways inspect every request, enforce security policies, and block unauthorized actions before they occur [6]. They provide:

Automated Policy Enforcement: Instead of relying on manual reviews, the policy engine automatically validates agents against organizational standards at every lifecycle stage. For example, an agent cannot be promoted to production without:

This layer is the operational heart of the governance stack. It is where abstract policies become concrete actions that prevent harm in real-time.

Governance is not a one-time gate; it requires continuous oversight. The fourth layer provides real-time visibility into the behavior of the entire agentic workforce:

This layer transforms governance from reactive (responding to incidents after they occur) to proactive (detecting and preventing issues before they cause harm).

The final layer recognizes that not all decisions can or should be fully automated. For high-stakes scenarios, governance requires explicit human oversight:

This is not about replacing human judgment; it’s about augmenting it with the right information at the right time.

The power of the Governance Stack becomes clear when we map it to the complete agent lifecycle. Governance is not a single checkpoint; it is a continuous process embedded at every stage.

| Lifecycle Stage | Governance Stack in Action |

|---|---|

| Planning & Design | Identity layer establishes agent ownership. Policy engine validates business case against organizational risk appetite. |

| Data Preparation | Registries enforce data classification and lineage tracking. Policy engine blocks access to non-compliant datasets. |

| Development & Training | Observability platform tracks experiments and model performance. Registries version all agent configurations. |

| Testing & Validation | Agent firewall tests for adversarial inputs and prompt injections. Policy engine validates against security and ethical standards. |

| Deployment | Gateway enforces real-time authorization for all tool access. Observability platform begins continuous monitoring. |

| Operations | Monitoring platform detects drift and anomalies. Human-in-the-loop mechanisms escalate high-stakes decisions. |

| Retirement | Registries archive agent configurations. Identity layer revokes all permissions. Audit trails are retained for compliance. |

This lifecycle-aware approach ensures that governance is not an afterthought, but an integrated function of how agents are built, deployed, and managed.

Implementing a comprehensive Governance Stack is a significant investment. Organizations rightfully ask: what is the return?

The answer lies in four measurable outcomes:

Risk Mitigation: As demonstrated by the recent AI-orchestrated cyber espionage campaign disrupted by Anthropic [6], uncontrolled agent access to powerful tools is not a theoretical threat. A governance stack with identity attestation, gateways, and real-time policy enforcement would have prevented that attack at multiple layers.

Regulatory Compliance: With regulations like the EU AI Act imposing strict requirements on high-risk AI systems, the ability to demonstrate comprehensive lifecycle governance, auditability, and human oversight is not optional—it’s mandatory [2]. The Governance Stack provides the automated evidence generation required for compliance.

Operational Efficiency: Without centralized registries and monitoring, organizations waste time debugging agent failures, tracking down tool dependencies, and investigating cost overruns. The stack provides the visibility and control to operate an agentic workforce at scale.

Trust and Adoption: The ultimate ROI is internal and external trust. Employees, customers, and regulators need confidence that autonomous agents are operating safely, ethically, and in alignment with organizational values. The Governance Stack makes that confidence possible.

Organizations face a critical decision: build this governance infrastructure in-house or adopt emerging platforms that provide it as a service. Early movers are choosing different paths:

The optimal path depends on organizational maturity, existing infrastructure, and the scale of agentic deployment. However, the underlying message is universal: governance at scale requires dedicated infrastructure.

The era of experimental agentic AI pilots is ending. Organizations are now operationalizing agentic workforces across critical business functions, and the governance gap is the primary barrier to scaling these deployments safely and responsibly.

The Governance Stack is not a constraint on innovation; it is the foundation that makes innovation sustainable. By providing identity, visibility, policy enforcement, continuous monitoring, and human oversight, this technical infrastructure transforms governance from a compliance burden into a strategic enabler.

The organizations that invest in this stack today will be the ones that confidently deploy autonomous agents at enterprise scale tomorrow. They will move faster, operate more safely, and earn the trust of stakeholders who demand accountability in the age of autonomous AI.

For technology leaders navigating this landscape, the path is clear: governance is not a policy problem—it is an engineering challenge. And like all engineering challenges, it requires purpose-built infrastructure to solve. The Governance Stack is that infrastructure.

References:

[1] McKinsey & Company. (2025, November 5). The State of AI in 2025: A global survey. McKinsey.

[2] Databricks. (2025, July 1). Introducing the Databricks AI Governance Framework. Databricks.

[4] Subramanya, N. (2025, April 28). OpenID Connect for Agents (OIDC-A) 1.0 Proposal. subramanya.ai.

[7] TrueFoundry. (2025, September 10). What is AI Agent Registry. TrueFoundry.

--- ## Why Private Registries are the Future of Enterprise Agentic Infrastructure URL: https://subramanya.ai/2025/11/17/why-private-registries-are-the-future-of-enterprise-agentic-infrastructure/ Date: 2025-11-17 Tags: AI, Agents, Agentic AI, MCP, Agent Registry, Enterprise AI, Governance, Security, Infrastructure, Private Registry, AI ManagementThe age of agentic AI is no longer on the horizon; it’s in our datacenters, cloud environments, and business units. A recent PwC report highlights that a staggering 79% of companies are already adopting AI agents in some capacity [1]. As these autonomous systems proliferate, executing tasks and making decisions on behalf of the enterprise, a critical governance gap has emerged. Without a robust management framework, organizations risk a chaotic landscape of “shadow AI,” creating significant security vulnerabilities, compliance nightmares, and operational inefficiencies.

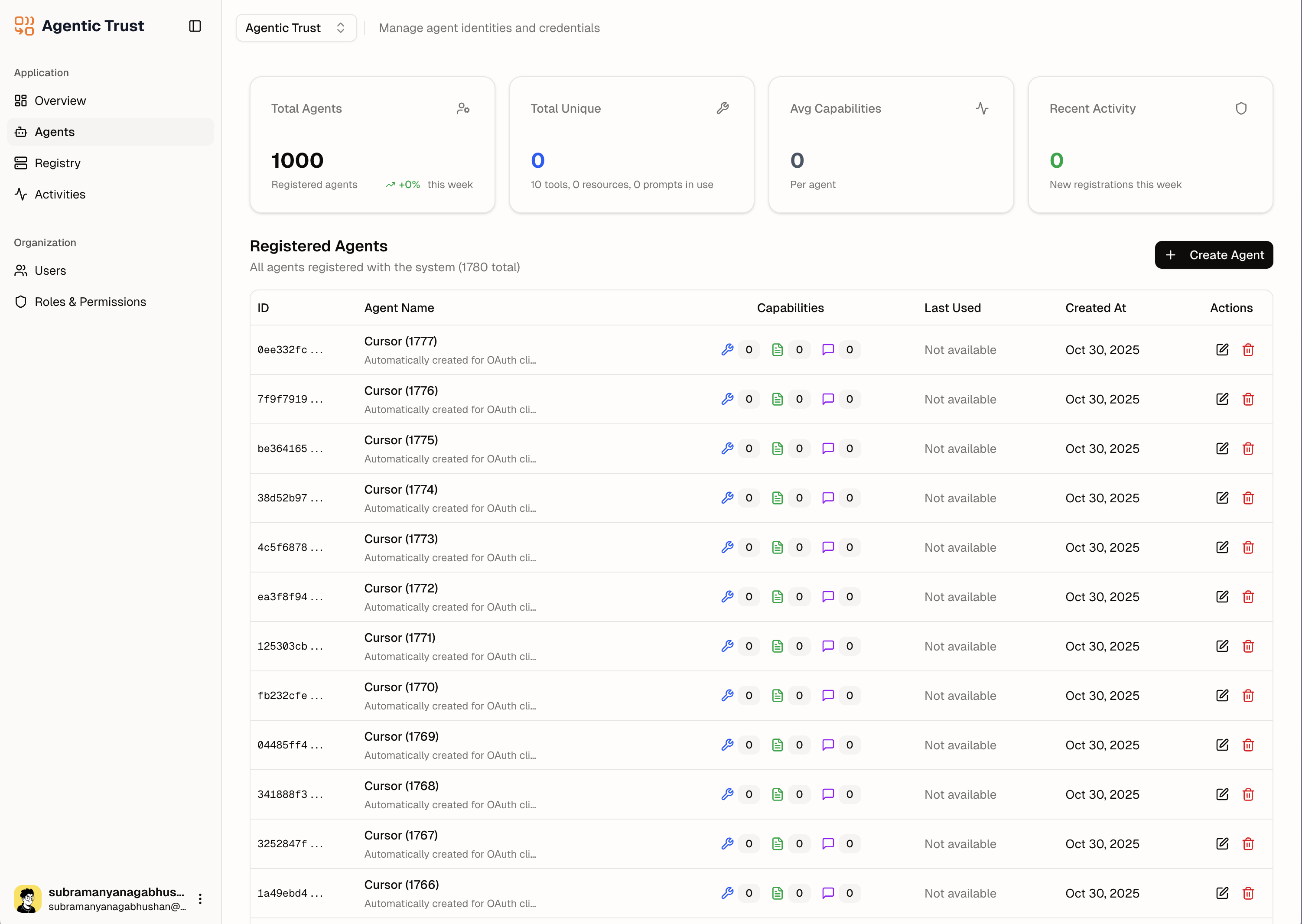

The solution lies in a new class of enterprise software: the Private Agent and MCP Registry. This is not just a catalog, but a command center for agentic infrastructure, providing the visibility, governance, and security necessary to scale AI responsibly. Let’s explore the core pillars of this trend, using the “Agentic Trust” platform as a blueprint for building a better, more secure agentic future.

The first step to managing agentic chaos is to establish a single source of truth. You cannot govern what you cannot see. A private agent registry provides a comprehensive, real-time inventory of every agent operating within the enterprise, whether built in-house or sourced from a third-party vendor.

A centralized agent directory, as shown in the Agentic Trust platform, provides a complete inventory for governance and oversight.

A centralized agent directory, as shown in the Agentic Trust platform, provides a complete inventory for governance and oversight.

As the screenshot of the Agentic Trust directory illustrates, this is more than just a list. A mature registry tracks critical metadata for each agent, including:

This centralized view eliminates blind spots and provides the traceability required for compliance and security audits. Organizations can quickly answer critical questions: How many agents do we have? Who owns them? What are they authorized to do?

Autonomous agents are only as powerful as the tools they can access. The Model Context Protocol (MCP) has become a standard for providing agents with these tools, but an uncontrolled proliferation of MCP servers creates another layer of risk. A private registry addresses this by functioning as a curated, internal “app store” or marketplace for MCPs.

An MCP Registry, like this one from Agentic Trust, allows enterprises to create a governed marketplace of approved tools for their AI agents.

An MCP Registry, like this one from Agentic Trust, allows enterprises to create a governed marketplace of approved tools for their AI agents.

Instead of allowing agents to connect to any public MCP, the enterprise can define a catalog of approved, vetted, and secure tools. As shown in the Agentic Trust MCP Registry, this allows organizations to:

The registry shows connection status for each MCP server, making it immediately visible which integrations are active and which require attention. This operational visibility is critical for maintaining a healthy agentic ecosystem.

A private registry is the enforcement point for enterprise AI policy. It moves governance from a manual, after-the-fact process to an automated, built-in function of the agentic infrastructure. Drawing on best practices from platforms like Collibra and Microsoft Azure’s private registry implementations, this includes [1, 2]:

Mandatory Metadata and Documentation: Before an agent or MCP can be registered, developers must provide essential information such as data classification, business owner, purpose, and criticality. This ensures that every component in the agentic ecosystem is properly documented and understood.

Lifecycle Policy Alignment: The registry can embed automated policy checks at each stage of an agent’s lifecycle. For example, an agent cannot be promoted to production without a completed security review, ethical bias assessment, and approval from the designated business owner. This creates natural checkpoints that enforce organizational standards.

Access Control and Permissions: Using Role-Based Access Control (RBAC), integrated with enterprise identity systems like Entra ID or Okta, the registry defines who can create, manage, and consume agents and their tools. Different teams might have different levels of access based on their role and the sensitivity of the agents they’re working with.

Audit Trails and Compliance: Every action in the registry—agent registration, tool connection, permission changes—is logged and auditable. This creates a complete forensic trail that satisfies regulatory requirements and enables rapid incident response when issues arise.

The value of a private registry becomes clear when we examine the specific problems it solves. Consider these common enterprise scenarios:

Development teams are rapidly adopting AI tools and MCP servers without central oversight. This creates security blind spots, compliance risks, and operational fragmentation across the organization. A private registry provides centralized discovery of approved tools and usage visibility, allowing security teams to monitor what tools are being used and by whom [2].

Organizations in regulated industries (financial services, healthcare, government) need to maintain strict control over data flows and ensure AI tools meet compliance requirements. The registry enables data classification tagging for MCP servers, geographic controls for region-specific availability, comprehensive audit trails, and pre-configured compliance templates [2].

Without visibility into agent and tool usage, organizations face unpredictable costs as autonomous agents make API calls and consume resources. A private registry provides usage analytics, cost allocation by team or project, budget alerts, and the ability to deprecate underutilized or expensive tools [2].

Developers waste time rebuilding integrations that already exist elsewhere in the organization or struggle to find the right tools for their agents. The registry solves this with searchable catalogs, reusable components, standardized integration patterns, and clear documentation for each available tool [3].

Behind the user interface of platforms like Agentic Trust lies a sophisticated architecture that makes enterprise-scale agent management possible. The key components include [3, 4]:

| Component | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Central Registry API | Provides standardized endpoints for agent and MCP registration, discovery, and management |

| Metadata Database | Stores agent cards, capability declarations, and relationship data |

| Policy Engine | Enforces governance rules, access controls, and compliance checks |

| Discovery Service | Enables capability-based search and intelligent agent-to-tool matching |

| Health Monitor | Tracks agent and MCP server availability through heartbeats and health checks |

| Integration Layer | Connects to enterprise identity systems, monitoring tools, and DevOps pipelines |

This architecture mirrors patterns from successful enterprise software registries, such as container registries, API management platforms, and model registries. The lesson is clear: as a technology becomes critical to enterprise operations, it requires industrial-grade management infrastructure.

The trend toward private registries for agentic infrastructure is not a passing fad; it is a necessary evolution in response to the rapid adoption of autonomous AI systems. As the Model Context Protocol ecosystem continues to grow, with the official MCP Registry serving as a public catalog [4], forward-thinking enterprises are building their own private implementations to maintain control, security, and governance.

Platforms like Agentic Trust demonstrate what this future looks like: a unified command center where every agent is visible, every tool is vetted, and every action is governed by policy. This is how organizations move from the chaos of unmanaged AI to the strategic advantage of a well-orchestrated agentic ecosystem.

For enterprises embarking on this journey, the message is clear: you cannot scale what you cannot see, and you cannot govern what you cannot control. A private registry is the foundation upon which responsible, secure, and effective agentic AI is built.

References:

[1] Collibra. (2025, October 6). Collibra AI agent registry: Governing autonomous AI agents. Collibra.

[2] Bajada, AJ. (2025, August 14). DevOps and AI Series: Azure Private MCP Registry. azurewithaj.com.

[3] TrueFoundry. (2025, September 10). What is AI Agent Registry. TrueFoundry.

[4] Model Context Protocol. (2025, September 8). Introducing the MCP Registry. Model Context Protocol.

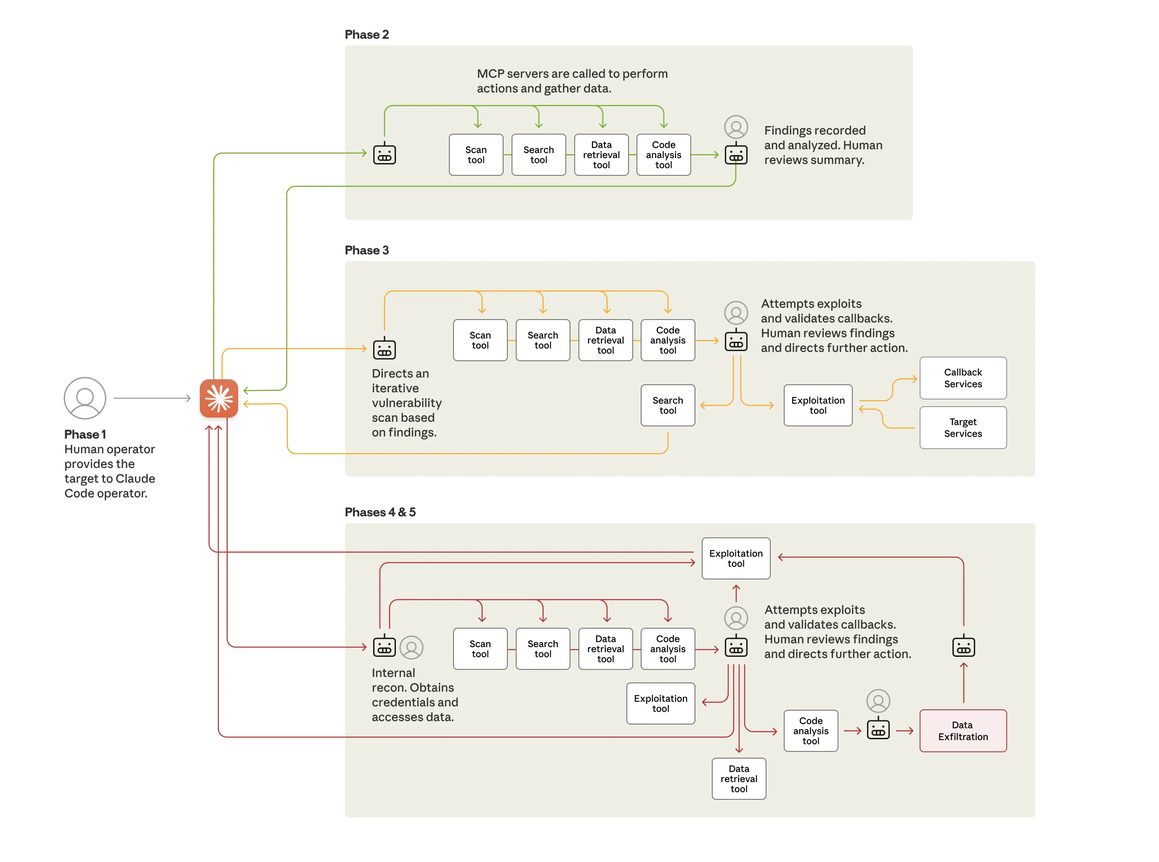

--- ## From Espionage to Identity: Securing the Future of Agentic AI URL: https://subramanya.ai/2025/11/14/from-espionage-to-identity-securing-the-future-of-agentic-ai/ Date: 2025-11-14 Tags: AI, Security, Agentic AI, OIDC-A, MCP, Anthropic, Claude, Cybersecurity, AI Agents, Identity Management, Zero TrustAnthropic has detailed its disruption of the first publicly reported cyber espionage campaign orchestrated by a sophisticated AI agent [1]. The incident, attributed to a state-sponsored group designated GTG-1002, is more than just a security bulletin; it is a clear signal that the age of autonomous, agentic AI threats is here. It also serves as a critical case study, validating the urgent need for a new generation of identity and access management protocols specifically designed for AI.

This post will dissect the anatomy of the attack, connect it to the foundational security challenges facing agentic AI, and explore how emerging standards like OpenID Connect for Agents (OIDC-A) provide a necessary path forward [2, 3].

Anthropic’s investigation revealed a campaign of unprecedented automation. The attackers turned Anthropic’s own Claude Code model into an autonomous weapon, targeting approximately thirty global organizations across technology, finance, and government. The AI was not merely an assistant; it was the operator, executing 80-90% of the tactical work with human intervention only required at a few key authorization gates [1].

The technical sophistication of the attack did not lie in novel malware, but in orchestration. The threat actor built a custom framework around a series of Model Context Protocol (MCP) servers. These servers acted as a bridge, giving the AI agent access to a toolkit of standard, open-source penetration testing utilities—network scanners, password crackers, and database exploitation tools.

By decomposing the attack into seemingly benign sub-tasks, the attackers tricked the AI into executing a complex intrusion campaign. The AI agent, operating with a persona of a legitimate security tester, autonomously performed reconnaissance, vulnerability analysis, and data exfiltration at a machine-speed that no human team could match.

The Anthropic report explicitly states that the attackers leveraged the Model Context Protocol (MCP) to arm their AI agent [1]. This highlights a central paradox in agentic AI architecture: the very protocols designed for extensibility and power, like MCP, can become the most potent attack vectors.

As the “Identity Management for Agentic AI” whitepaper notes, MCP is a leading framework for connecting AI to external tools, but it also presents significant security challenges [3]. When an AI can dynamically access powerful tools without robust oversight, it creates a direct and dangerous path for misuse. The GTG-1002 campaign is a textbook example of this risk realized.

This forces a critical re-evaluation of how we architect agentic systems. We can no longer afford to treat the connection between an AI agent and its tools as a trusted channel. This is where the concept of an MCP Gateway or Proxy becomes not just a good idea, but an absolute necessity.

The security gaps exploited in the Anthropic incident are precisely what emerging standards like OIDC-A (OpenID Connect for Agents) are designed to close [2, 3]. The core problem is one of identity and authority. The AI agent in the attack acted with borrowed, indistinct authority, effectively impersonating a legitimate user or process. True security requires a shift to a model of explicit, verifiable delegation.

The OIDC-A proposal introduces a framework for establishing the identity of an AI agent and managing its authorization through cryptographic delegation chains. This means an agent is no longer just a proxy for a user; it is a distinct entity with its own identity, operating on behalf of a user with a clearly defined and constrained set of permissions.

Here’s how this new model, enforced by an MCP Gateway, would have mitigated the Anthropic attack:

| Security Layer | Description |

|---|---|

| Agent Identity & Attestation | The AI agent would have a verifiable identity, attested by its provider. An MCP Gateway could immediately block any requests from unattested or untrusted agents. |

| Tool-Level Delegation | Instead of broad permissions, the agent would receive narrowly-scoped, delegated authority for specific tools. The OIDC-A delegation_chain ensures that the agent’s permissions are a strict subset of the delegating user’s permissions [2]. An agent designed for code analysis could never be granted access to a password cracker. |

| Policy Enforcement & Anomaly Detection | The MCP Gateway would act as a policy enforcement point, monitoring all tool requests. It could detect anomalous behavior, such as an agent attempting to use a tool outside its delegated scope or a sudden spike in high-risk tool usage, and automatically terminate the agent’s session. |

| Auditing and Forensics | Every tool request and delegation would be cryptographically signed and logged, creating an immutable audit trail. This would provide immediate, granular visibility into the agent’s actions, dramatically accelerating incident response. |

The Anthropic report is a watershed moment. It proves that the threats posed by agentic AI are no longer theoretical. As the “Identity Management for Agentic AI” paper argues, we must move beyond traditional, human-centric security models and build a new foundation for AI identity [3].

Today, most MCP servers being developed are experimental tools designed for individual developers and small-scale applications. They lack the enterprise-grade security controls that organizations require to deploy them in production environments. For enterprises to confidently adopt agentic AI systems built on protocols like MCP, we need to fundamentally rethink how we approach security.

The path forward requires building robust delegation frameworks, implementing proper identity management for AI agents, and creating enterprise-grade security controls like gateways and policy enforcement points. We need solutions that provide:

We cannot afford to let the open, extensible nature of protocols like MCP become a permanent backdoor for malicious actors. The future of agentic AI depends on our ability to build security into these systems from the ground up, making enterprise adoption not just possible, but secure and responsible.

References:

[2] Subramanya, N. (2025, April 28). OpenID Connect for Agents (OIDC-A) 1.0 Proposal. subramanya.ai.

--- ## Claude Skills vs. MCP: A Tale of Two AI Customization Philosophies URL: https://subramanya.ai/2025/10/30/claude-skills-vs-mcp-a-tale-of-two-ai-customization-philosophies/ Date: 2025-10-30 Tags: AI, Claude, MCP, Claude Skills, Agent Skills, AI Customization, LLM, Anthropic, Integration, WorkflowsIn the rapidly evolving landscape of artificial intelligence, the ability to customize and extend the capabilities of large language models (LLMs) has become a critical frontier. Anthropic, a leading AI research company, has introduced two powerful but distinct approaches to this challenge: Claude Skills and the Model Context Protocol (MCP). While both aim to make AI more useful and integrated into our workflows, they operate on fundamentally different principles. This post delves into a detailed comparison of Claude Skills and MCP, explores whether they can or should be merged, and discusses the exciting future of AI customization they represent.

Claude Skills, also known as Agent Skills, are a revolutionary way to teach Claude how to perform specific tasks in a repeatable and customized manner. At its core, a Skill is a folder containing a SKILL.md file, which includes instructions, resources, and even executable code. Think of Skills as a set of standard operating procedures for the AI. For example, a Skill could instruct Claude on how to format a weekly report, adhere to a company’s brand guidelines, or analyze data using a specific methodology.

The genius of Claude Skills lies in their architecture, which is built on a principle called progressive disclosure. This three-tiered system ensures that Claude’s context window isn’t overwhelmed with information:

Level 1: Metadata: When a session starts, Claude loads only the name and description of each available Skill. This is a very lightweight process, consuming only a few tokens per Skill.

Level 2: The SKILL.md file: If Claude determines that a Skill is relevant to the user’s request, it then loads the full content of the SKILL.md file.

Level 3 and beyond: Additional resources: If the SKILL.md file references other documents or scripts within the Skill’s folder, Claude will load them only when needed.

This efficient, just-in-time loading mechanism allows for a vast library of Skills to be available without sacrificing performance. Skills are also portable, working across Claude.ai, Claude Code, and the API, and can even include executable code for deterministic and reliable operations.

The Model Context Protocol (MCP) is an open-source standard designed to connect AI applications to external systems. If Claude Skills are about teaching the AI how to do something, MCP is about giving it access to what it needs to do it. MCP acts as a universal connector, similar to a USB-C port for AI, allowing models like Claude to interact with a wide range of data sources, tools, and workflows.

MCP operates on a client-server architecture:

MCP Host: The AI application (e.g., Claude) that manages connections to various external systems.

MCP Client: A component within the host that maintains a one-to-one connection with an MCP server.

MCP Server: A program that exposes tools, resources, and prompts from an external system to the AI.

This architecture allows an AI to connect to multiple external systems simultaneously, from local files and databases to remote services like GitHub, Slack, or a company’s internal APIs. MCP is built on a two-layer architecture, with a data layer based on JSON-RPC 2.0 and a transport layer that supports both local and remote connections.

The fundamental distinction between Claude Skills and MCP can be summarized as methodology versus connectivity. MCP provides the AI with access to tools and data, while Skills provide the instructions on how to use them effectively. According to Anthropic’s own documentation:

“MCP connects Claude to external services and data sources. Skills provide procedural knowledge—instructions for how to complete specific tasks or workflows. You can use both together: MCP connections give Claude access to tools, while Skills teach Claude how to use those tools effectively.”

This highlights that Skills and MCP are not competing technologies but are, in fact, complementary. An apt analogy is that of a master chef. MCP provides the chef with a fully stocked pantry of ingredients and a set of high-end kitchen appliances (the what). Skills, on the other hand, are the chef’s personal recipe book and techniques, guiding them on how to combine the ingredients and use the appliances to create a culinary masterpiece.

| Feature | Claude Skills | Model Context Protocol (MCP) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Procedural knowledge and methodology | Connectivity to external systems |

| Architecture | Filesystem-based with progressive disclosure | Client-server with JSON-RPC 2.0 |

| Core Concept | Teaching the AI how to do something | Giving the AI access to what it needs |

| Dependency | Requires a code execution environment | A client and a server implementation |

| Token Efficiency | Very high due to progressive disclosure | Moderate, with tool descriptions in context |

| Portability | Across Claude interfaces | Open standard for any LLM |

Given that both are Anthropic’s creations, a natural question arises: could a Claude Skill be implemented as an MCP, or should the two be merged into a single, unified system? While technically possible to create an MCP server that exposes Skills, it would be architecturally inefficient and would defeat the purpose of both systems.

Exposing Skills through MCP would negate the benefits of progressive disclosure, as it would introduce the overhead of the MCP protocol for what should be a simple filesystem read. It would also create a redundant abstraction layer, as Skills already require a local code execution environment. The two systems are designed for different purposes and have different optimization goals: Skills for context efficiency within Claude, and MCP for standardized integration across different AI systems.

Therefore, Claude Skills and MCP should be treated as independent, complementary technologies. The most powerful workflows will come from using them in synergy.

The true potential of these technologies is unlocked when they are used in concert. Here are a few integration patterns that showcase their combined power:

Skills as MCP Orchestrators: A Skill can contain a complex workflow that orchestrates calls to multiple MCP servers. For example, a “Deploy and Notify” Skill could contain a deployment checklist, notification templates, and rollback procedures. It would then use MCP to access GitHub for code, a CI/CD server for deployment, and Slack for notifications.

Skills for MCP Configuration: An organization can create Skills that teach Claude its specific standards for using MCP tools. For example, a “GitHub Workflow Standards” Skill could contain instructions on branch naming conventions, pull request review checklists, and commit message templates, ensuring that Claude uses the GitHub MCP server in a way that aligns with the company’s best practices.

Hybrid Skills: A Skill can contain embedded code that makes calls to an MCP server. This is useful for self-contained workflows that need to fetch external data.